Intraoperative Somatosensory Evoked Potentials

With our patient population getting older (the motor conduction slows by 0.4–1.7 m/s per decade after 20 years and the sensory by 2–4 m/s), overweight (conduction velocity of motor and sensory nerves decreases as BMI increases) and sicker (many diseases cause changes to conduction velocity), it’s understandable why our intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials aren’t always textbook.

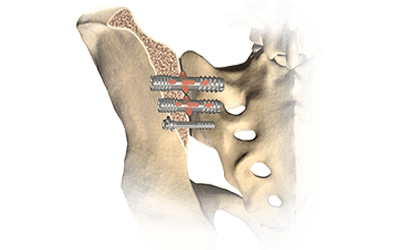

Image from http://bit.ly/11FQFPP

And this is especially true for lower extremity intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. One reason for this is due to the longer tracts and amount of temporal dispersion of the sensory signals.

Temporal Dispersion reflects the conduction velocities of the fastest and slowest nerve fibers. This is due to slower fiber conduction reaching the recording electrode later than faster fibers.

The greater the level of temporal dispersion, the greater the difference in conduction velocities, the worse off your SSEP data will replicate. Remember, these averaged responses are additive and show larger amplitudes when many axons fire and reach the recording electrode at a similar time. That gives us nice sized amplitudes at predictable times.

But when the response times are all over the place, these additive potentials can look variable.

“But the patient feels everything, and can move their limbs, why don’t you have SSEP data?” – says the surgeon.

Usually, we can get reliable SSEP data. But there’s always that case where we can’t get anything to trace consistently, even with a patient that is “neurologically intact.”

But a variable response is not the same as an absent response.

Fibers that fire at different velocities, due to slowing, may give you a nice trace one time, and then a poorer trace the next time. This is different than fibers that won’t summate, or are blocked along the way, which are more likely to show very flat data (low amplitude, late latency, possibly nothing at all).

How To Handle Variable Intraoperative SSEP

Let’s say you’re monitoring the lower extremity SSEP. You superimpose the first 3 traces collected and they look dead on. You even take out your markers and see that there is only a 5% difference in amplitude height from the smallest to largest wave.

Great! And if things stay that way, then you’ll be pretty confident to make a call if there is a significant change off of baseline SSEP (make sure you read about when to set those baseline SSEP in my previous post). Even if the change is only a 40% reduction, you’d still be wise to inform the surgeon (the 50/10 rule is not gospel).

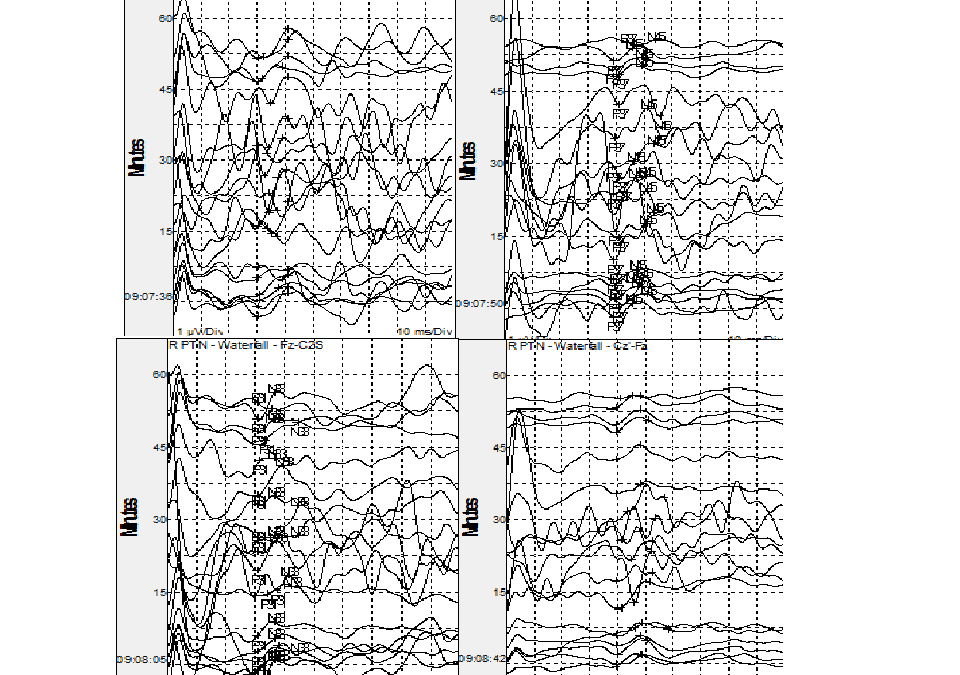

But what if your 82-year-old diabetic with a BMI of 43.66 kg/m^2 doesn’t have such clean data? What if after your first 3 traces, there is a 38% change from the smallest to largest amplitude?

Crap. You’re probably getting the feeling that this is going to be one of those cases where you’re going to scare yourself over nothing. Or even worse, possibly talk yourself out of making a call with a significant change. While a 38% change in your fist 3 traces is a lot, you should definitely continue to collect traces and get a better understanding what the trial-to-trial variability of the patient’s responses is going to be… especially once you’ve done everything in your power to reduce noise, maximize filter settings, double-check for optimal recording and stimulating electrode placement, etc.

Your baselines should be set at a level that represents the patient’s “most likely” (or best guess average) amplitude. You want to choose your baseline to be a trace with an amplitude that best depicts the summation of that nerve at that level of (hopefully steady state) anesthesia. You’ll want to use your waterfall window to best come to this conclusion after the patient has had time to adapt to the medication on board.

If the traces remain variable but around same level, you may decide that you can monitor the case. If so, make sure the surgeon knows about the difficulty of recording your SSEP, your level of confidence to monitor the case effectively, what might be the cause of the variable data, etc.

If the traces are even worse (say >50% difference in amplitude from trace-to-trace), you may decide that the data is unreliable. Inform the surgeon that while there are responses coming from the activation of the nerve, that it’s not reliable enough to monitor with any confidence. You need to be able to make a call of a 50% decrease off of your baseline. If the amplitude might change greater than that from trace-to-trace, you have no way to give reliable information to the surgeon. No monitoring is better than bad monitoring.

Is this a common problem?

It really depends on the patient population that you are seeing. If you work with a bunch of 20-year-old patients, your success rate in obtaining reliable intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials will be high. If you are working with a lot of patient’s with polyneuropathies, trauma or other neurological deficits, your success rate will be lower.

Most studies will show that it’s not as bad as tcMEP (though I have read the opposite too). But I think most will relate to what’s said in Sloan’s 2008 paper…

[socialpoll id=”2365394″]

Optimizing SSEP Traces

So you turned up your stim intensity and stared at the head leads for an additional 15 seconds. Everything is plugged in correctly. Time to hang it up?

No. Now it’s time to change variables and try to make improvements. You now have some sort of starting range (something to 38% range). That’s what you’ll use as your benchmark.

What you do next is up to what you have in front of you. Here’s an example:

If there are some peripheral nerve issues, maybe you start testing more proximal stimulation sites. Seems reasonable until you notice the nurse struggling to put in a Foley. You can either stand over his shoulder until he’s done (and risk being called a perv) or get to work on your settings.

Deciding to stay in your corner and be productive with the time you have, you elect to change the rep rate to something a little slower. But that’s going to take too long to collect, so you elect to do multipulse stimulation as a quicker test. That’s been shown to help in diabetic patients.

The nurse finally got his Foley and immediately calls for the scrub tech to start to drape. Never mind the rep rate for now. You dart over to the patient and put in some additional stimulating electrodes. You toss the ends down towards the feet and have now given yourself some additional options.

Peeking over at anesthesia as you head back to your seat, you see they are keeping a steady state on what was agreed upon. You decide to head back to your table, test the new stimulation site, rep rates, head lead positions, filter settings, ask for ketamine drip, etc.

Before skin incision, you let the surgeon know exactly where you’re at in the process, what else you need to check, what you’re seeing vs what you’d like to see, and feedback from the neurologist if the current data is reliable or not. If the surgeon elects to go ahead at that point, you update him/her after you have extinguished all options and give a general opinion on your confidence in the data.

Oh, ya… document it all.

Keep Learning

Here are some related guides and posts that you might enjoy next.

How To Have Deep Dive Neuromonitoring Conversations That Pays Off…

How To Have A Neuromonitoring Discussion One of the reasons for starting this website was to make sure I was part of the neuromonitoring conversation. It was a decision I made early in my career... and I'm glad I did. Hearing the different perspectives and experiences...

Intraoperative EMG: Referential or Bipolar?

Recording Electrodes For EMG in the Operating Room: Referential or Bipolar? If your IONM manager walked into the OR in the middle of your case, took a look at your intraoperative EMG traces and started questioning your setup, could you defend yourself? I try to do...

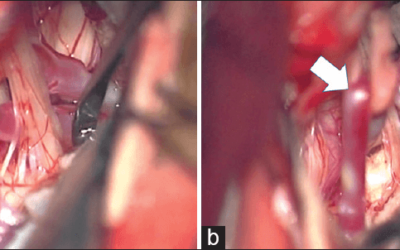

BAER During MVD Surgery: A New Protocol?

BAER (Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials) During Microvascular Decompression Surgery You might remember when I was complaining about using ABR in the operating room and how to adjust the click polarity to help obtain a more reliable BAER. But my first gripe, having...

Bye-Bye Neuromonitoring Forum

Goodbye To The Neuromonitoring Forum One area of the website that I thought had the most potential to be an asset for the IONM community was the neuromonitoring forum. But it has been several months now and it is still a complete ghost town. I'm honestly not too...

EMG Nerve Monitoring During Minimally Invasive Fusion of the Sacroiliac Joint

Minimally Invasive Fusion of the Sacroiliac Joint Using EMG Nerve Monitoring EMG nerve monitoring in lumbar surgery makes up a large percentage of cases monitored every year. Using EMG nerve monitoring during SI joint fusions seems to be less utilized, even though the...

Physical Exam Scope Of Practice For The Surgical Neurophysiologist

SNP's Performing A Physical Exam: Who Should Do It And Who Shouldn't... Before any case is monitored, all pertinent patient history, signs, symptoms, physical exam findings and diagnostics should be gathered, documented and relayed to any oversight physician that may...