There’s a quote that goes something like this: “what’s the definition of conflict? Two people in the same zip code…”

Why? Because we’re programmed for it. We prioritize survival and reproduction over everything else. Contrast is an edge in survival and selecting a fit mate.

In some cultures, like in the USA, purposeful contrast is a guiding principle for progress. We defected to a land with the promise of no religious rule. Land of the free grants permission to freely question anything, celebrate discovery, and find your way as an individual. It’s the freedom to create something unique and valuable, be it a company in an industry or your own personal brand.

There are always, however, 2 sides to every coin.

The invention of the ship was also invention of the shipwreck.

Paul Varilio

Contrast creates conflict.

Conflict theory discusses the outcomes of opposing forces in society created through contrast. While harmony is an option, tension is omnipresent and the status quo is always the enemy.

For instance, there’s plenty of space for Ford and Chevy to compete, even cooperate. The opportunity of competition creates friction and breeds conflict. It doesn’t matter if it is a friendly competition or if shots have been fired, conflict will ensue.

As contrast drives a wedge of distinction, incentives change for those involved. In this post, we will use Game Theory and model each person engaged in conflict as a rational actor – at least as a starting point – and anticipate self-interest as the primary strategy. In the game of chicken, this means each player’s interest is aimed at the highest payout, or getting the other person to swerve off the road before they do. Swerving in tandem (coordinating) doesn’t win the status. A collision is catastrophic.

The conflict due to contrast stacks the incentives unproportionate.

Temptation > Coordination > Neutral > Punishment

We find modeling the game of chicken useful when looking at the anticipated actions of ourselves, our teams, our company, our industry, etc. Remember, it’s a model, so it’s not accurate. But it might be helpful.

The Game of Chicken

The math used in game theory can get harry, but there’s still plenty to gain by just touching it at a surface level. So let’s break it down conceptually before we watch it play out in the real world.

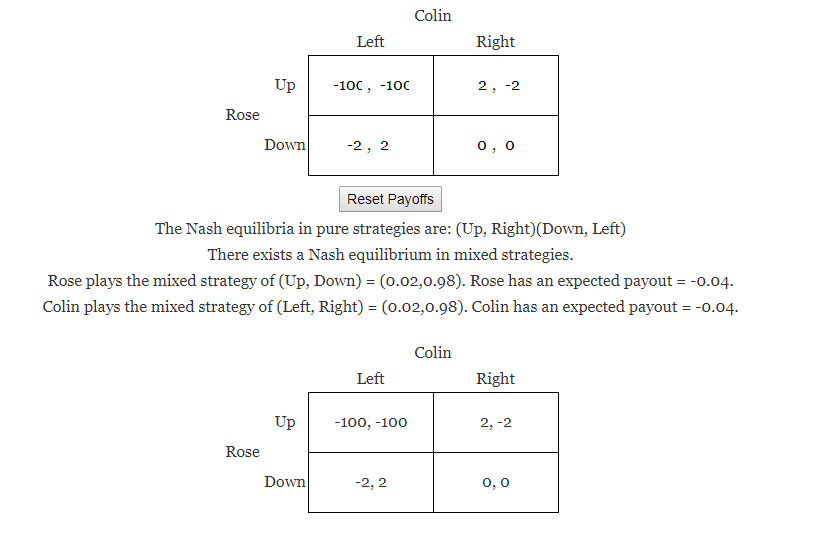

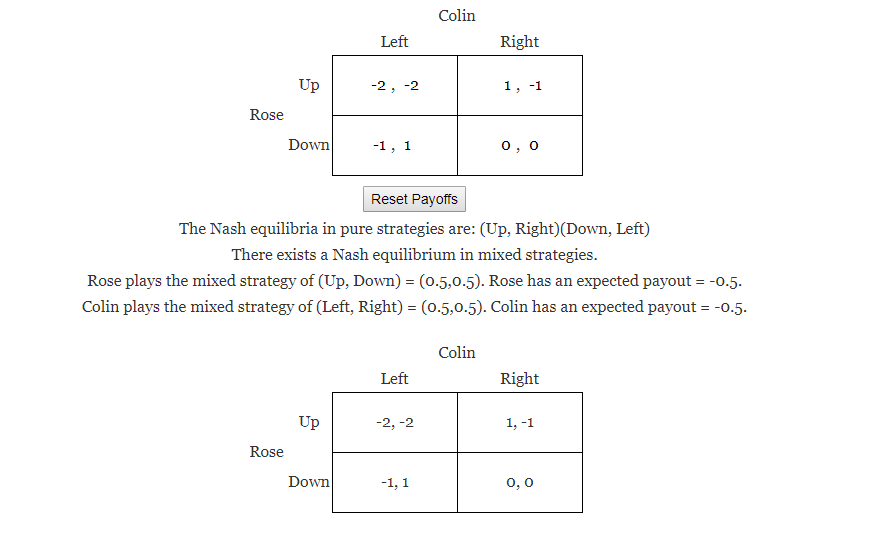

If we had 2 people playing chicken, Rose and Colin, we can see that each of them only has 2 options: swerve or drive straight. (Apologies for the confusion in my image below. Change out Up and Left for “Straight,” and Down and Right for “Swerve.” Rose is the left number in each box, Colin is the right.)

- If Colin and Rose both end up going Straight-Straight they both score -100. That’s a huge loss compared to the other opportunities but justified since we’re talking life/death here.

- In Straight-Swerve and Swerve-Straight, the winner gets 2. The loser gets -2.

- In Swerve-Swerve, they both get 0. (Or maybe -1 if they are both considered chickens).

- Here, they know the most likely outcomes of the other player and there is no better option for them. For instance, if Colin thinks Rose is going straight, he is better off swerving than going straight. Straight = -100 and Swerve =-2. When he considers Rose swerving, he is better to go straight than swerve. Straight = 2 and Swerve = 0. Because the payout for Straight-Straight is so severe, he should swerve no matter what.

- Rose is making the best decision she can, taking into account Colin’s decision while his decision remains unchanged, and Colin is making the best decision he can, taking into account Rose’s decision while her decision remains unchanged (Nash Equilibrium in mixed strategies).

- This game ends up being a losing proposition for both players, as their expected payout is negative (if they played this to infinity, which is impossible).

The Game of Chicken in Real Life (and in Hollywood)

Hollywood is in the business of conflict and the game of chicken is all about the inevitability of conflict. The game of chicken presents an environment where self-interested agents play with nothing/little to win and risk a heavier downside. Fueled by pride, the goal is to not back down. It’s often depicted as part of being young and dumb (an age group willing to up the ante from a game of war of attrition to life or death situation of chicken).

What Can’t Kevin Bacon Teach Us?

Here’s an example from Footloose where they’re playing by the most common game rules (with the least common vehicle, the 5 mph tractor). Headed on a crash course with each other, the winner holds true while the loser swerves.

The real twist here is that the audience, and Kevin Bacon, have more information than the guy on the other tractor. Kevin Bacon knows his laces are stuck; he’s not playing an even game of chicken.

On that narrow road, swerving into the creek could be worse than colliding. Since the information isn’t known to the other guy, his math is unchanged. Kevin Bacon’s math changes, as he has no other choice than to move forward. Straight or swerve.

If Kevin Bacon told the other guy his laces were tied, the other would have to update his priors. A dip in the drink doesn’t seem so bad.

Manager’s lesson #1: understand the game each person is playing, as well as how the environment is set up. For example, the person trying to get fired isn’t acting irrationally when they tell you they aren’t covering the case starting at 5 pm. They removed their steering wheel, strapped themselves to the seat, or did anything else that takes out the option of “swerve.” In those instances, you really want to swerve as early as possible. A collision is only a matter of time and that’s too costly to endure. The best option, usually, is to give them what they want and terminate their employment.

That’s a tough call to make, as well as one to identify (sometimes). Terminating their employment here isn’t about not being a chicken, it’s about protecting the remainder of the team.

George Costanza Lives a Life of Conflict

The person incentivized to stay the course is much more likely to do so. Consider the game of chicken George Costanza is playing with the government. They are going to pay him to continue unemployment, so he’s going to work hard to not have to work hard. Now, this game is probably considered a “war of attrition” where each side is not too concerned about the collision. They have more incentives to get the other side to swerve/concede, comparatively.

Manager Lesson #2: If you (or your company’s processes) incentives a game of chicken or war of attrition, you really need to see that as the problem, not the person playing the game. If you need someone to travel to cover a case out of the area and do not have a formal, fair process in place, each team member is incentivized to ignore the request (assuming traveling earns (-) points in their eyes – some people like to travel). You’re better off changing the incentives to a positive, bring clarity to expectations, encourage a culture of cooperation, and/or adapting process than yelling/punishing your team.

Kiefer Sutherland’s Face: Signal or Noise?

Yet another version of the game is seen in Stand By Me. Here, we see a slight variation in the game. There is a third party, the truck coming down the road. Neither of the cars in the game of chicken “lost,” yet the innocent third party crashed off the road. This game’s “winner” is the one most willing to accelerate into danger. The loser keeps on going with a bruised ego. The real loser is the truck, or collateral damage, as the result of the game.

Also of note are the signals of the players in the game. Posturing, threats, taunts, multipliers (drinking beer) are all tactics to win.

Manger Lesson #3: There are often other losers in the game of chicken when it affects others. Be mindful of collateral damage. As an example, I’ve seen a game of chicken played between an IONM company (no longer in operation) and their internal education team. As the financial safety net was being taken from their operations team (feel free to read that as available cash reserves gone), reactive cost-cutting measures took place. The incentives to train the new hires were no longer in line with the prior agreement and the game started. The group of new hires going days without any contact during their training period, with no change in the date to start in the OR, had the largest cost.

Manager Lesson #4: A manager who thinks in bets is better suited to take in all the information, update their priors, and better predict the outcomes. Game theory assumes rational actors, yet reality is quite a different story. Make decisions about signal vs noise depending on the safe assumption of being right (historical data might be helpful) and place a weight on it. You’ll never be able to read minds or predict the future, but you can be less wrong. Stack the chips in your favor and make the best decision. I think the writers wanted us to bet heavy on Keifer not swerving.

The Kiss of Death

The last game here is from Rebel without a Cause. It demonstrates the ultimate game of chicken, where the loser loses their car and the winner loses their life.

Manager’s Lesson #5: This is an extreme example. Most managers will pick up on it and eliminate the game before it gets started. The harder one to fix is the game where the negative outcomes are palatable in small doses. But this is just one arm of a toxic culture. Corporate culture, individual actors, or even poor planning are all suspects.

Manager’s Lesson #6: This is a lose:lose game. The winner lost his car, the loser his life (and car). A classic example is the posturing seen between sales and marketing, where incentives are pulling them in different directions. You can usually see a game of chicken when you hear “that’s not my job” coming up.

Manager’s Lesson #7: Does anyone else want that girl on their team? She not only enables the game to be played but added fuel to the fire. We shouldn’t pass right over the fact that she gave a very intimate kiss to the first driver before sending him off to risk his life over nothing, but then she’s just handing out dirt to anyone asking for it? No thanks.

Final Thoughts

When managers go through a hiring process, they’re looking not only for the right person for the job but the right person for the company/team. They’re taught tactics to identify givers, takers, and matchers. Takers, obviously, are willing to compete hard in a game of chicken.

Where managers fall short (I got my hand raised here) is neglecting to look for an environment where takers thrive, like the game of chicken. Neuromonitoring managers should look to change the rules, change the incentives, and work to create a microculture of cooperation before enacting punishment on those forced into the game.