Beliefs Are Identities

In hindsight, it was obvious. It almost always is.

But this one seems like a real head smacker. I don’t need any modern equipment; 30 minutes and a playground and my 2 boys will make a bulletproof case for handwashing. Their fingernails will look as if they’ve been scratching tar.

But dirty hands were the problem the medical profession had problems getting past. Doctors found it insulting to be considered “dirty.” They wouldn’t change their minds because it threatened how they saw themselves.

They chose ego over outcomes.

It’s a story we should all know in neuromonitoring, seeing as a lot of what we do lives in the gray. There’s not one clear-cut way to practice, but there are clues as to which probably works best. As more studies demonstrate optimal practices, we have to allow our current selves to act rationally and forgive our past selves so our future selves can act better.

Before jumping into changing our minds on recommended anesthetic requests for CEA surgeries, let’s walk through the story of doctors with dirty hands.

Handwashing’s Gory Story

Semmelweis probably came up with similar examples as my kids with dirty nails but met harsher critics than I’d expect I would.

His suggestion was made to a hospital where physicians had 3X the incidence of puerperal fever (sometimes fatal to the moms) than the midwives.

It probably sounded something like this:

“Hey, Dr. Dirt-merchant. Wash your hands and squeeze this lime.”

OK, he was a physician and a scientist, so it was probably nicer and smarter than that. But whatever he said, it didn’t work. The other docs took offense to it and mocked him (and continued to have worse outcomes).

Reports state that he got increasingly more vocal about the ignored issue, lost his mind, was sent to an insane asylum by his peers, and was beaten to death by the guards a couple of weeks later.

Maybe there’s an angle to take here on Dr. Semmelweis’ inability to persuade others, but the more glaring problem here is how the other physicians couldn’t change their own minds.

What Went Wrong Here?

Was it because Dr. Semmelweis was only able to demonstrate empirical evidence but not provide a solid theory as to the cause (Pasteur and Lister cleared things up later)?

No, that was how most medicine was practiced in the 1800s. Remember, the go-to move was bloodletting.

The problem was more likely due to belief perseverance, which means being more worried about being right than getting it right, even when you’re wrong.

The story highlights an ongoing problem in the scientific community, which includes current healthcare and neuromonitoring.

And you and me too.

When we see something that matters — knowing our kneejerk tendency is to dismiss — we should purposely sit with the counterpoint a little longer. If we see something that challenges a strong opinion, perk up and pay attention.

TIVA for CEA Using EEG and SSEP?

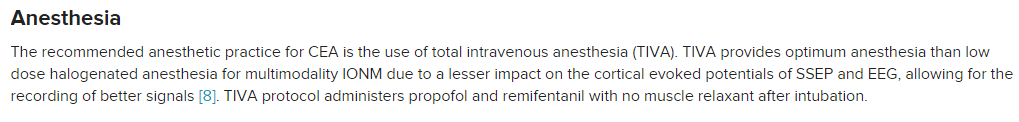

Well, this just happened to me. Here’s a snippet from the article that challenged a longstanding understanding of mine:

Why TIVA For CEA Caught Me Off Guard

I can tell you I’ve never recommended TIVA for a CEA case. Not to the anesthesiologist I work with, nor any surgical neurophysiologist I’ve trained. But then again, I’ve never recommended a mix of nitrous and iso, yet that’s been shown to work too.

Now, I’ve had the unfortunate luck of having a couple of cases where the anesthesia team added in Propofol just prior to clamping. That wiped out my EEG, but adding Propofol to Sevo/Des is not the same as TIVA.

The anesthetics protocol I’ve always requested is < 1 MAC of an inhalational agent + muscle relaxation.

I’ve also had the debate of adding tcMEP to the protocol to better monitor the deep white matter. It makes sense on paper since that is a blind spot for EEG and SSEP (the motor portion of deep tracts).

In theory, it adds to catching a potential deficit. But, as the saying goes, in theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not.

I’m too reluctant to risk EEG during CEA. It’s the gold standard. Watching enough EEGs slow or go into burst suppression during spine cases with TIVA has left me too nervous to make that trade.

Adding in tcMEP without TIVA exposes me to an unacceptable level of false positives compared to not using it. The additional area covered has a historically low incidence of stroke, as well as a questionable medical intervention should it be identified. If you look at the literature on EEG + SSEP for CEA, it’s a dynamic duo that gets as good as anything else in neuromonitoring.

So if I’m thinking in bets (probabilistically), I can’t bet on TIVA. Not betting as in TIVA isn’t defensible (because it is), but betting that it’s optimal.

And through the rest of my ramblings here, that’s what I want you to hold onto. Remember to think as to what is optimal, not defensible.

How To Derail Your Thinking

But here’s the problem. The paper’s author, Faisal, is really, really good at this IONM thing. He’s published a lot. More importantly, people I respect give nothing but the highest remarks about him.

We should stay open-minded regardless, but that increases the tension.

Do I:

1) Remember all the times my smooth brain got me in trouble in the past? Faisal is the researcher and all. Plus, I haven’t done any TIVA CEA cases. Maybe there’s something I’m missing? But then again, I’m also aware of expertise bias and don’t want to fall for that shortcut just to save a couple of calories.

2) Fall back on what I know is true. Seriously, I’ve done a ton of these cases over the years and try to keep up with the literature and what’s presented at conferences. But I also know I’m more likely to stick up for what I already hold as true, a feature of being human and all.

Taking either of those thought paths is problematic. It’s also an example of why sometimes more information (author’s name) might not lead you to a better decision.

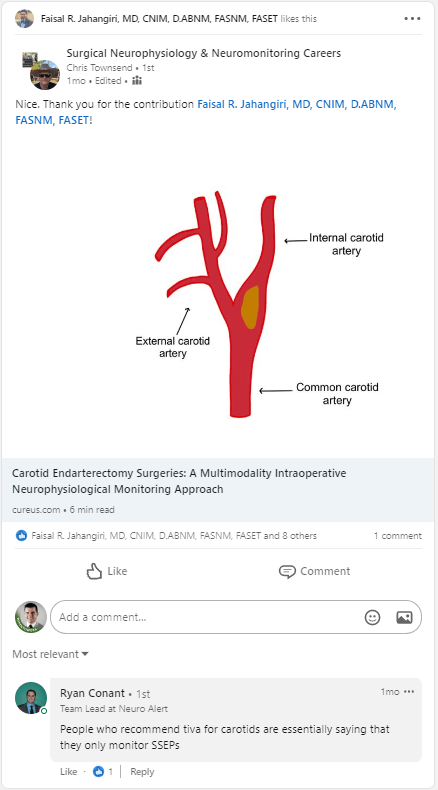

Then I see this on LinkedIn the other day:

Seeking Confirmation, Not Information Is A Problem

First, I see Chris endorsing it. That means he either accepts TIVA as a recommended protocol, didn’t notice it, or didn’t decide to mention it there. Hmm, he’s been in this field for quite some time too.

Then I scroll down to see Ryan’s comment. Yes, this! That’s what I’ve been saying for years, just slightly different. A team lead for a good company + confirmation.

No. Stop.

This isn’t the right way to go about this. This line of thinking is right in line with what prevented Dr. Semmelweis’ work from gaining acceptance.

There’s not enough context, discussion, or proof presented. Coming to a conclusion this way is lazy.

This is the third wrong decision path I could take. All shortcuts, which is a feature of your brain, not a bug. But when we are faced with something where we have expected repeated encounters + time to sit with the problem longer, we should override our tendency to efficiency and aim for accuracy.

What we need to do here is unlearn — that takes effort.

Unlearning

Dr. Semmelweis’ peers were afflicted with the same problem as me, even without all the noise we have today. It’s not a matter of scarce or abundant information. The problem is our shared ancestry and DNA-encoded tendencies to fit in with the tribe, which we see expressed as our biases.

So how do we fight fire with fire? How can we use what we’ve got to better position ourselves to take in information and make the best decisions?

Observe Better.

Our brains are primarily resourcing allocators by predicting future events through learned past patterns and genetic makeup. Appreciating how emotions affect both learning and memory, we should look to be more granular in our recognition and our defining of them.

In this instance, we have chosen to undertake a purposeful pursuit of insight. Here, we target moments that unlocks the emotion which forever changes one’s reality: surprise.

Insights and Surprise

For those with a curious itch, surprise is the pleasurable sensation of a scratch. It means there’s potentially something going on that you were not straight on. An opportunity to learn and gain new insights.

That’s what happened when I read the TIVA protocol for carotid endarterectomies. I was surprised, so I took note.

Surprise tends to fall into one of three categories where insights are potential outputs.

First, we can gain insight by looking for something that’s changed and connecting them.

That’s all evolution is, right? There is some critical item that has become more scarce that causes an increase in competition which results in adaptation. We adapt to better meet the new world. It’s no different in how a company acts to new reimbursement changes, how neuromonitoring clinicians view the CNIM after increased hospital adoption, or even how the dinosaurs evolved into birds.

If something looks surprising, look for what’s become scarce. Connect those and you can better predict what behaviors follow as people compete.

For example, did TIVA use different drugs than the historical Propofol + Remi, like when there was a Propofol shortage? What did that change in the environment? Maybe using Dex allowing less Propofol in the TIVA protocol is a game-changer, but I’ve never experienced it.

The second way is to look for something that doesn’t fit the patterns we’ve seen in the past.

It’s usually some sort of intuition that has you thinking, “hmm, that’s weird.” There’s a contradiction somewhere.

Search for that irregularity and try to uncover insight; you might have your own Moneyball moment.

For example, has there been improvement in BIS monitoring technology allowing for anesthesiologists to use less propofol to accomplish their goals?

The third, most common and most difficult to work with, is when you catch a moment of surprise because you’re faced with something that is counter to your understanding.

This is what we’ve been discussing here. It’s when something needs to be corrected.

For example, TIVA is better than <1 MAC of Sevo for CEA challenges my current beliefs with the potential of a needed correction.

“The “preliminary” step of locating possibilities worthy of explicit consideration includes steps like: weighing what you know and don’t know, what you can and can’t predict; making a deliberate effort to avoid absurdity bias and widen confidence intervals; pondering which questions are the important ones, trying to adjust for possible Black Swans”

― How to Actually Change Your Mind

How Do We Put This Into Action?

First, we need to look at what people and companies say about themselves vs. what they actually do.

Not stopping to look for moments of insight is a missed opportunity for the person looking to be curious. There is merit to the Toyota way, allowing the six sigma ninjas do their thing. But treating everything like a manufacturing processes falls short when looking for big gains. Always pushing for efficiency and error reductions purposely restricts moments of chaos and new lessons learned. Variation is what fuels it.

For example, Dr. Cohen thought to test using 4 electrodes for tcMEP, Dr. MacDonald thought to record cortical SSEPs using montages outside of best practices, and Dr. Dong tried out multipulse tcMEP stimulation for facial nerve monitoring.

Their curiosity led them to this path by saying things like “what if.” Their insights changed the way they deliver patient care by asking “what did we learn.”

Similarly, companies may look to drop the overused, underachieved “innovation” company value for a more obtainable one: insight.

One insinuates creating something new as an inventor might, while the other is allowing a greater surface area to discover something else useful as an investigator might.

If we look at the past 20 or so years in IONM, the investigators have made more headway than the inventors.

To Be One Thing, You Can’t Be Another

That’s a tough one to operationalize because managers (guilty here) are trying to optimize for things to run smoothly. You are far more likely to face punishment should things go bad than praise should you unearth a valuable insight. The weights are typically imbalanced to incentives caution.

Remember, a company’s culture answers the question “people around here that do this get promoted, people that do that don’t.” It is incentives that get us to act and culture that guides us on how to behave.

As a result, we create a feedback loop to prevent errors at all costs. We default to thoughts of how to fix it when things go wrong. This is not a breeding ground for insight, nor an easy place to get to as an organization.

Start With Signaling

While there is plenty of tactics one could elect to use in order to adapt, one example can be borrowed from the medical profession. Pre- and postmortems signal to employees that errors are expected, but so are insights.

Postmortems let you ask questions like “what went right and what went wrong… and what can we do differently?”

Premortems lets you uncover what could go wrong and what to do, if anything, beforehand. It might even open up discussion about dropping a plan, product, or service before it gets started for something better.

Both acknowledge errors and chaos. It reframes how failure is viewed, allowing individuals to try new things. And that’s a recipe for not only insights and innovation, but employee engagement.

It Starts With Culture To Set The Norms, Then The Teams Can Act Within Those Guidelines

After a company has decided how to act — expect errors to happen and treat them as learning experiences — the individual is unshackled from fear. Fear to try out new things. Fear to speak up when they need help. Fear to dig in deeper to expose other problems in the pursuit of insights.

There are plenty of other tactics besides pre and postmortems that can and should be used. But now that we’ve got those in place, the individual can start to act.

Ask Better Questions

But before we get to actions, we need to start where it matters the most: the questions. Oftentimes, it is asking better questions that get the best answer. Why, by how much, what else, and how confident am I are good starting points.

Drilling down questions helps expose new perspectives that might reveal solutions beyond the superficial level.

It also helps us give weight to our understanding.

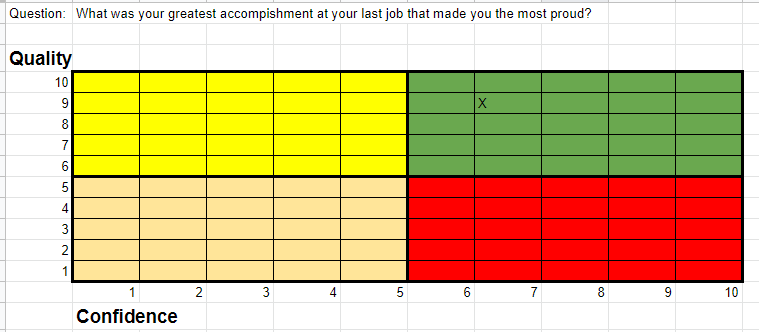

How To Properly Weigh Answers To Our Questions

Here’s a tactic I use when interviewing surgical neurophysiologists. It helps me place context to each question asked. Here’s the gist of it:

– Establish the true need of the team and then develop questions around those needs

– Create a 2X2 matrix that shows how well the person answered the question by how confident you are in that assessment.

– Compare your assessment to the others interviewing that person.

How do I adapt my interview framework to see if I should change my mind about using TIVA for carotidectomy surgery with EEG and SSEP over a sub-Mac request?

Well, I can grade my answers and how satisfied I am with them. The next step is to go looking for other information, as well as other perspectives on the confidence of each answer.

Phone a Friend

First, I’d tap my network and ask non-leading questions at first and then get down to specifics.

“Hey, you do a lot of CEA? What modalities do you use? What anesthetic protocol do you request? Why? Have you ever used TIVA? What was the difference? If you haven’t, how do you think it would go? What are you basing that on and how confident are you? Have you heard any other groups doing things differently? Have you read any studies making suggestions or comparing anesthetic techniques?”

(At the risk of influencing you what to think instead of how to think, my results here were: sub-Mac inhalational as optimal)

Hunt for Information

The next test would be to do some additional research. Maybe there’s a paper out there that has asked and answered this exact question?

Just reading through papers, you’ll be able to find many different protocols being used. Sub-MAC (sevoflurane, isoflurane or desflurane) or no more than 50% N2O , Propofol with co-administration of Dexmedetomidine, propofol infusion at 2 μg/mL, intermittent fentanyl boluses, and sevoflurane with MAC of 0.3–0.4, and TIVA.

If you look at the outcome of each of these different protocols on EEG and SSEP, it’s similar.

It’s not that way for all anesthetics, but the more common ones we’ll encounter. (This paper on anesthetics on EEG gives a really nice breakdown of the mechanisms.)

It does not, however, compare the degree of EEG effects compared to achieving the goals of anesthesia. And that’s a piece of the puzzle I am missing.

Stress Test Your New Information and Perspective

What we don’t want to happen is to learn some new information and then let that override what we currently understand. It’s difficult to change one’s mind once you hold it in there as true, but once you do, it can also be hard to not “go all in.”

We need to level-set our emotions.

One such activity might be using your brain’s tendencies to your advantage by going through thought experiments to better predict the future. Imagine stating your position to some of the smartest people in that field. Would they agree with you, or tear you a new one? If there were any rebuttals, could you field those and hold your position as optimal (not just defensible)? Can you predict what they’d say?

In this exercise, we want to hold conversations to the constraints of finding what’s optimal. Ansers to quickly settle a dispute, like”There’s more than one way to skin a cat…” have no place here.

You’re now better situated to compare your new position to your priors. If the points made supersede your previous opinion on paper, then it might be time to test it out. If your priors stand the assault, that position should be strengthened. When an idea goes up against counterfactuals and persists, that’s a great signal of getting to optimal.

Where I Landed

My base case is EEG + SSEP using sub-MAC inhalational agent + roc provides the optimal monitoring for carotid endarterectomy when considering everything.

That’s where I started from previous learnings. If you’ve read enough of the literature, you know there’s not any clear winner.

Optimal is probably dependent on what happens during the case, but we don’t have the luxury to know that ahead of time.

As a result, holding a strong opinion here isn’t the best position to take. After speaking with peers, reviewing the literature, and stress testing my opinions to challenge biases, the results seem to be that “there’s more than one way to skin a cat” continues to be defensible, but clearly not optimal. Without really large studies comparing protocols, we’re left to connect some dots. For me, it’s what I’ve noticed in spine cases using EEG as a very rough estimate of the depth of anesthesia, where <1 MAC of inhalational agent seems to affect EEGs less than TIVA which acts as the tie breaker.

The upside is it does allow for flexibility. In these cases, you are better served to hunt for clues in your history and have discussions with the surgeon/anesthesiologist to cater to the specific needs of the patient in front of you.