I was asked to give a talk this year at an ASNM meeting in Tampa. The topics requested were all in the area of “things most people are afraid to do, so not spine or craniotomies.”

That left the door open and I decided to focus more on helping solve the problem of why people are reluctant to move onto doing “advanced” cases. Fear (expectancy) or task aversiveness (value) might act as accelerants, but it seems that our impulsiveness is the main driver of procrastination.

Probably better put, it derails long term objectives by defaulting to short term rewards. We’re hardwired to keep going to the honeypot, that which gives us those nice hits of dopamine and keeps our self-identity intact. There’s risk in doing anything else.

The Risk of Great Chili

And this, finally, set things up to talk about my chili. I honestly can’t believe I’ve made it 11 years without mentioning it here.

My chili, objectively and humbly speaking, changes lives. It’s that good. My parents, brothers, and friends all told me so.

And then one day, back from college, I went to a chili cookoff — you know, to make myself available in case anyone needed some advice. It was my first one, and things took an unexpected turn. Some people were using peppers I couldn’t pronounce, others spices I assumed no one used since Columbus’ time. This one tatted-up, monster of a man used whiskey in his chili, and then risked it all by adding a peach.

Each chili sampled was more humbling than the last. I realized my family was full of crap. Worse still, so was my chili.

No, no, no: bite my tongue. My chili brings people to their knees.

But while the heavenly spice of El Diablo (oh ya, I forgot to mention I named it) will tongue punch you into submission, it will never swim laps around one’s palate. I was a one-hit-wonder and I was in a chili rut very early in my chili career.

How did I get there here? Let’s backtrack a little.

After that soul-crushing dose of reality, I reflected on the errors of my way: I prioritized the wrong currency. I paid too much mind to collect the “attaboys” and ignored my own internal voice of curiosity screaming “what’s next?”. System 1 was so happy that system 2 never had a chance.

When it came to chili, as you’ll see, I was playing a finite game. There was a single short-term goal. A clear ending, which I haven’t mentioned. It wasn’t just the attaboys I was after, although that propelled me along. I was looking for a bigger status upgrade.

My ultimate plan looked like this: get enough accolades and then buy a chef’s hat. At 20 years old, I didn’t know much. But I knew this for a fact: if you wear a big hat without ridicule, you’ve made it.

The Big Hat Fallacy*

Yes, this is where it was all heading before the chili cookoff. I wanted a chef’s hat to wear while I prepared El Diablo. All the top dogs have big hats: the Pope, Lincoln, Pharrell, El Guapo. Like an extravagant chili garnish, a big hat signals greatness.

The perfect plan with no real downside. Would I have any concern about looking like a jackass?

No, a chef’s hat would symbolize I made it, and I was sure of it. I started on the ground floor with all the commoners but would now sit atop the mountain’s peak. If I gained enough accolades from my friends and family, I’d have the reserves to cash them in and silence any naysayers.

I was saving up to buy ego insurance, really.

At the festival, the painful realization kicked in. The new evidence presented allowed space for system 2 to get a word in. I was (at best, but not even) a cook collecting compliments.

A cook can slice and dice and serve up a tasty meal. Chop up this much of this, sprinkle in that, cook for this long. Sure, I was getting better, but at some point, I hit very real diminished returns. There’s only so much better you can make chili with the same ingredients. All this time, I was aiming at the wrong target.

All Hat, No Cattle

As any card-carrying member of CASI (Chili Appreciation Society International) will tell you, they know no endzone. The goal post is always moving in the infinite chili game they play.

Looking through this new lens, the chef’s hat seemed ridiculous. It no longer served the role of a trophy, just the functional purpose of keeping my hair out of the stew.

As I learned at the chili cookoff, when I went to use the attaboy currency in a market outside my own little ecosystem, the exchange rate sucked. I created my own tulipmania and that bubble burst. I was a phony clinging to his fool’s gold.

The rewards had to change to what matters, the chili, and less about my chili ego.

Show me the incentives and I will show you the outcomes.

– Charlie Munger

Now playing an infinite game, I moved to be internally focused and externally aware. That’s because there is no main dragon to slay or final line to cross. My own complacency, or bias to the status quo, is the omnipresent antagonist. Intrinsic, not extrinsic, motives push to defeat that foe.

With the new incentives in place, it became easier to see my opportunity cost. The time spent concentrated on perfecting what was already a winning recipe was time away from expanding my menu. I failed to step into any area uncomfortable and settled for the cozy familiar; the thing certain to get me an attaboy.

To go both wide and deep in the chili territory yet chartered, I needed to move beyond a cook and act as a chef would. Chefs tinker; they create; they explore. Curiosity would act as the scaffolding as I worked on constructing a bridge to the gap.

Curiosity, however, comes at a cost.

Chefs work curiously in a world accepting of failure. It’s the only way to actually be a chef. They end up making chili no one should ever eat. Batches that belong in the garbage. Mistakes.

I hate waste, so why even consider the additional work just for some scraped knees? Again, we look to incentives.

I was already “big hat” thinking about chili. I wanted to be a professional, not an amateur. I was ready to dawn that silly headdress in order to signal authority within that domain, even before I earned it (I’ll beg you to consider Hanlon’s razor here). With the new perspective of being a chef and not a cook, I desired to self-identify as unique, adaptive, and valuable (intrinsic motives). I couldn’t accept being anything less.

So I quit.

It wasn’t worth it. I wasn’t willing to commit the time. I never bought the chef’s hat. Making my dad call me Chef Joe in our kitchen was enough.

I did, however, carry that lesson over to the career I did choose. And this website was started as part of that process. It was part of my own process of acting as a chef would, as well as help others work to expand their menu. If you’ve ever read the section called “Meet Joe” at the bottom of the website, it sounds like I was one of the chili chefs at the cookoff.

Here’s the problem most surgical neurophysiologist face… their company spends a ton of money and time training to pass the CNIM (if you’re lucky) and then leave you to fend for yourself (AKA “The Spine Guy/Gal”). I’ve run across too many people without the opportunity to properly prepare for their boards, learn new case types, bounce ideas off other professionals and take their career to another level. This is my way of helping those looking to help themselves and move the profession forward at the same time.

It’s the chef’s perspective because I had my own chili experience. I know to look to play the long game and lean all the way in. I expect “the suck” because I’ve already decided it’s worth it. That means concentrate less on goals that act as the end-all-be-all and avoid trophies as the reward.

That said, how tempting are these shirts? Ok, I might be weaker than I let on…

Finally, Back to the Main Point

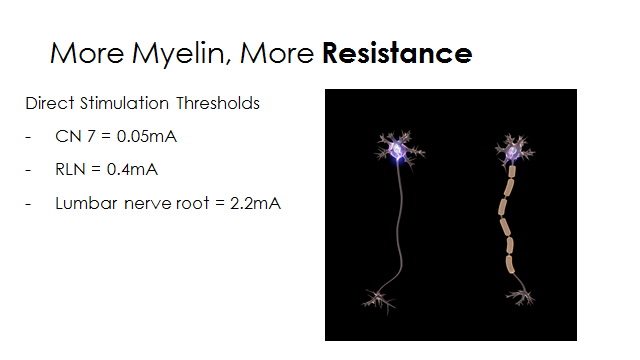

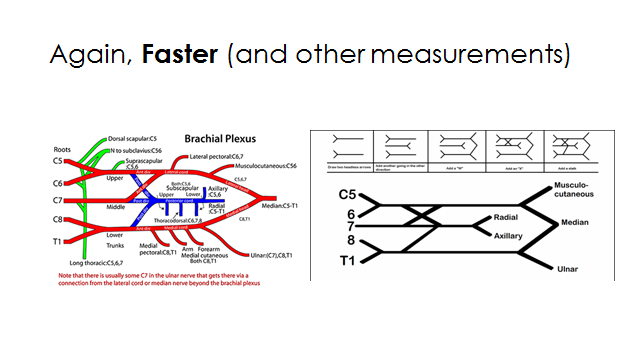

As surgical neurophysiologist, we spend a lot of time learning the nervous system. Most notably, the pathways. It’s almost as a plumber might look at some blueprints (if you’ll allow me to marginalize what it is we do for the sake of this analogy). Pump this handle and make it move through those pipes. Oh, you encountered some resistance? Either work to remove the obstacle or pump harder.

But the adjacent leap, studying the nervous system from a performance standpoint, shouldn’t sound like Greek to us. You know, neuroplasticity and all that.

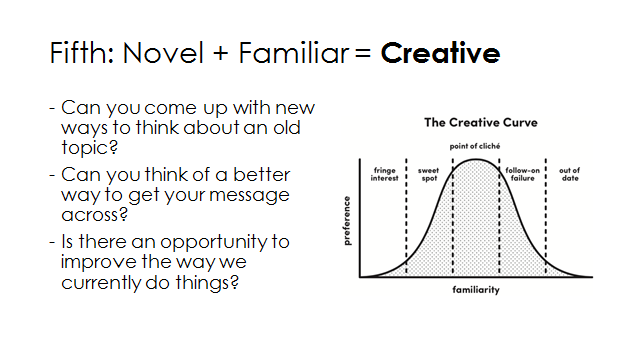

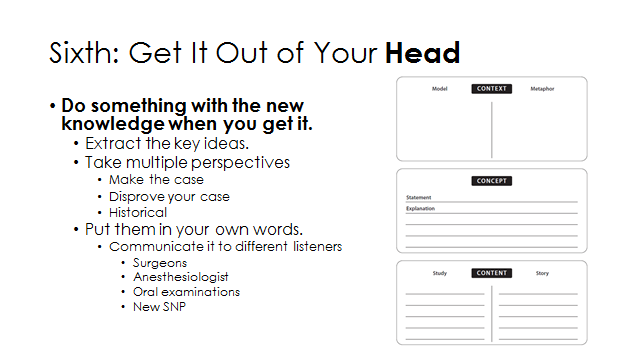

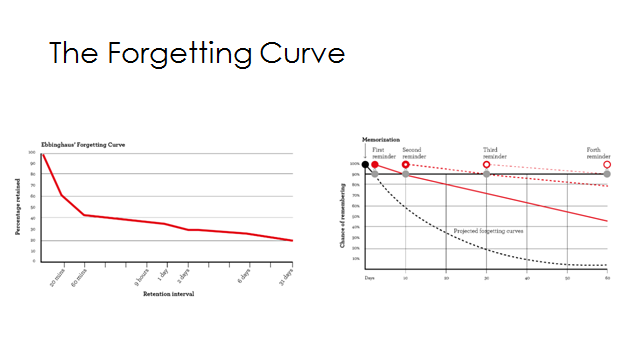

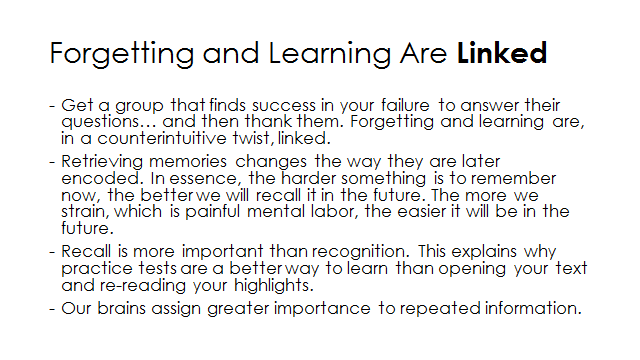

And that’s where I took the talk I gave after I blabbed about my chili for a while, if you can believe it. The ability to create an expansive menu results from recalling past experiences, patterns, and links. Our memory, which is fantastically flawed, doesn’t work well as a filing cabinet. It’s much better when we tag something as important by making connections to other memories, across different case uses, repeated over time.

And that’s how chefs are able to create where cooks can’t, and how neurophysiologist can widen their own competency.

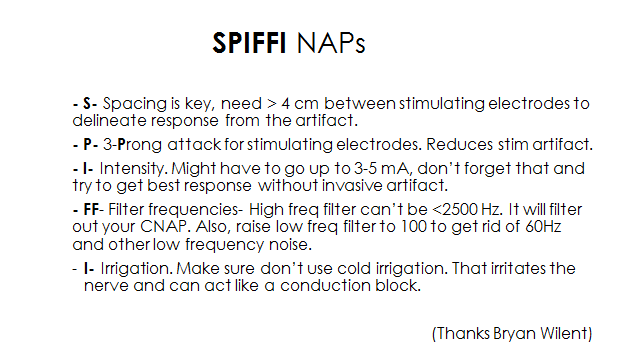

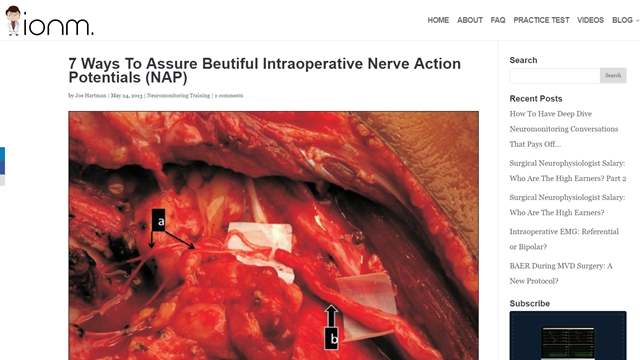

You can see the slide to it below, minus my what I’ve covered in my chili story above and all the technical NAP slides. I’ll hold back on those since the people in the crowd paid good money to be there and deserve those extras.

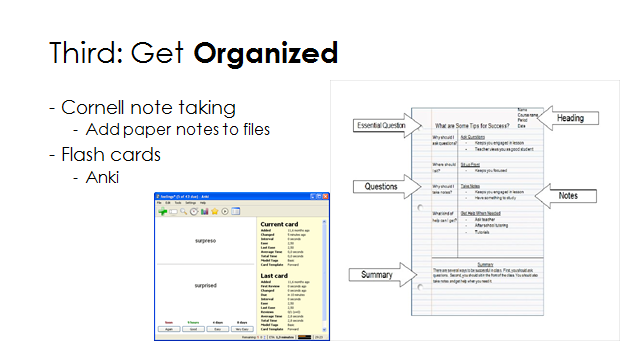

As an aside, I’m currently in the works of adding an automated system that follows the below Preparation, Product, and Process. Like my chili, I’m sure I’ll figure out an unoriginal name for it. Something like “second brain.” I don’t have it all figured out but could have something for both clinical and management available at some point in 2020. It’s really just for me and will probably let people at SpecialtyCare have access to it, but I’ll probably share the process at some point.

Slides from my talk

*Yes, I’ve been reading about heuristics, mental models, and fallacies. I even created my own here: the big hat fallacy. To me, wearing a big hat doesn’t represent the same level of fitness as a peacock’s feathers. The signaling cost isn’t the same.

** Imposter Syndrome – or thinking you’re not as qualified as you actually are. Dunning-Kreuger Syndrome – or why the most uninformed are the most confident.

If you’re interested in your own education or becoming part of your company’s education team, I recommend reading this book. A lot of the talk, and my own updated process, comes from it.