NOTE: At the time of this writing, we’re on the front side of the Coronavirus outbreak. I prefer to only write timeless over timely material, but there are certain moments in history that affects our IONM community.

This one feels really, really different. Our particular support role in healthcare has us on the battlefield, but not on the front line. The rapid spread of the virus has zapped critical supplies and has us largely on the sidelines at this point. That will change.

The past couple of weeks has the same feel of 9/11 in the sense of the emotional rollercoaster: denial, mourning, fear, anger, pride. Being global makes it bigger. This time, it feels like healthcare providers will earn the strong sense of gratitude and appreciation felt toward firefighters, first responders, and the police. I know most of the people reading this are in this role, so let me personally thank you for all you do.

In order to stay true to the educational purpose of the website, I thought it might be interesting to pull some of the big ideas being used to better understand what’s going on with the Coronavirus and how we can use that understanding in our own profession. Or maybe it works in the reverse order, where I put a spotlight on something that’s happening now and we can better understand the reason by comparing it to what we know in the OR.

As for the topic, it’s the speed at which this has all happened that stands out the most to me. It has left us with one overarching feeling: uncertainty. While we can work to manage risk, we have no control over what’s unknown. It’s a lesson in preparation, as well as a better understanding of what seems to be irrational human behavior in the moment.

Coronavirus: A Clear Case of Underreaction.

Humans have a hard time with numbers. And that’s why we’ve so obviously (ok, not really) missed the writing on the wall: a viral outbreak will crush us if we don’t contain it. Consider the following:

We tend to linearize exponential functions when assessing them intuitively. This “exponential growth bias” is a problem, especially when it’s early on and the numbers don’t seem too impressive. The positive feedback loop doesn’t have the teeth it soon will.

To say it another way, let’s look at the lilypads on a lake story. One lilypad starts out and reproduces another lilypad. They all double themselves every day. After 10 days, it’s still just a small spot in the pond. After day 20, it just starts to become noticeable. After day 29, it is half the lake. It takes only 1 more day to cover the entire lake. This is both obvious and surprising, just not at the same time.

Knowing how exponential growth works makes it a little easier to understand but it’s still hard in the moment. You can be looking out on the lake and not realize you have a lilypad problem until you’re into day 20+.

We saw that underreaction with the Coronavirus. We see it in the OR, too.

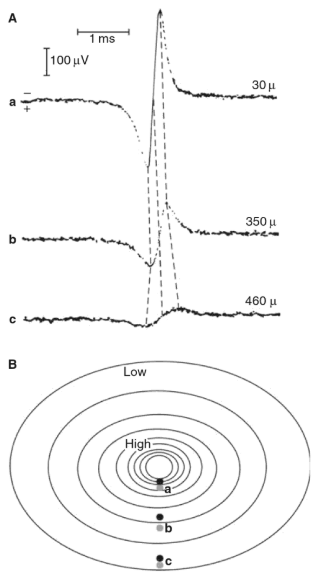

Try this: have a conversation with your colleague about changes in latency when recording a traveling potential at the elbow and at Erb’s point. This is a linear concept and easy enough to gauge. Next, discuss amplitude size/duration after distancing your recording electrode from the generator, which is an exponential change. Do you see how that’s harder to understand, recognize, and calculate?

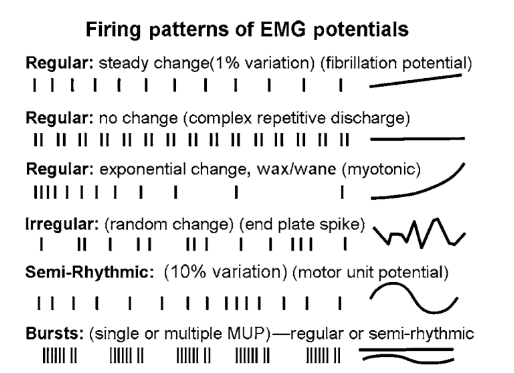

The whole thing can be a little confusing. But we have other examples that we can better visualize. What about the progression of EMG activity with a regular change in frequency (linear) vs myotonic discharges (exponential)?

It’s not that we’re broken. We’re just programmed to select what serves us best over time. Intuitively understanding the positive feedback loops of power laws isn’t in the DNA, and so we saw a spike in those underreacting to an exponentially building problem.

Going forward, we might look to stop ourselves in the moment and let System 2 thinking add some perspective to the conversation in our head. If our ego will allow us to be OK with looking wrong, we might be able to better recognize and prepare for major events on a non-linear trajectory and sidestep the cynical perspective our math-challenged, System 1 brain tends to take.

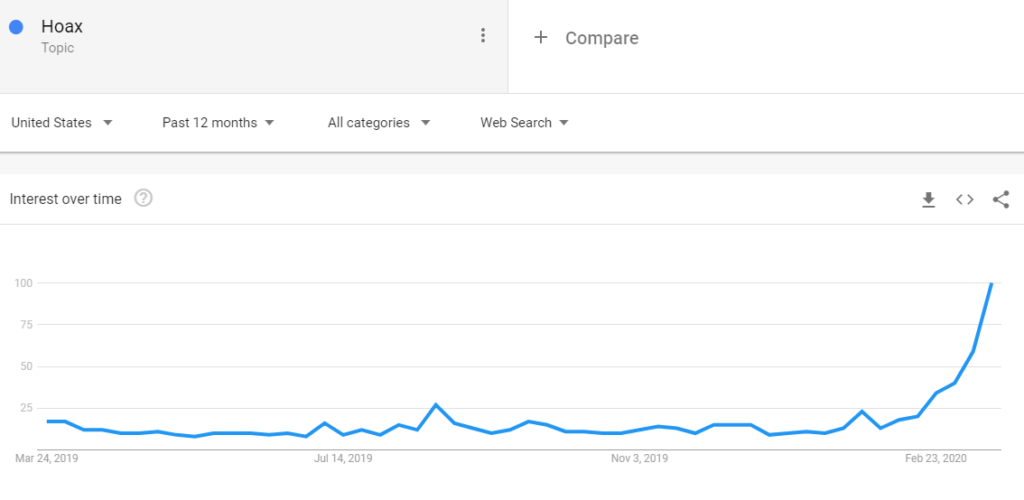

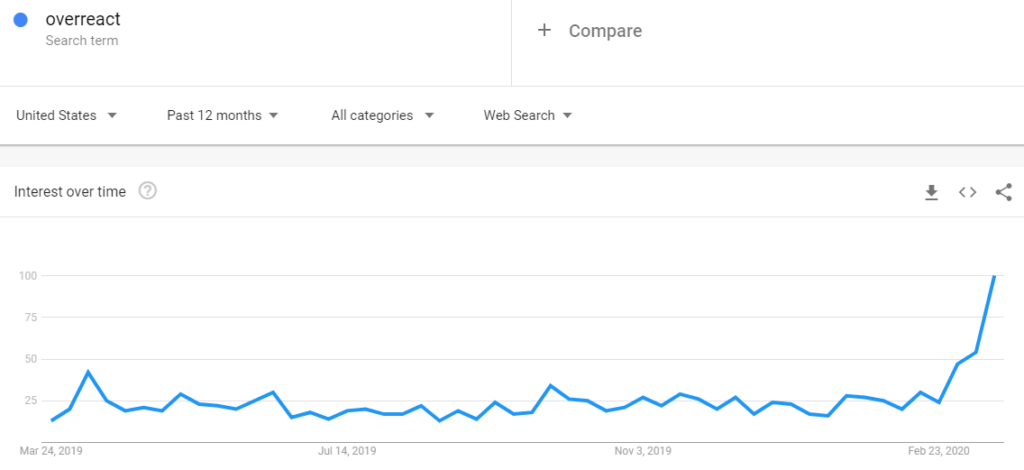

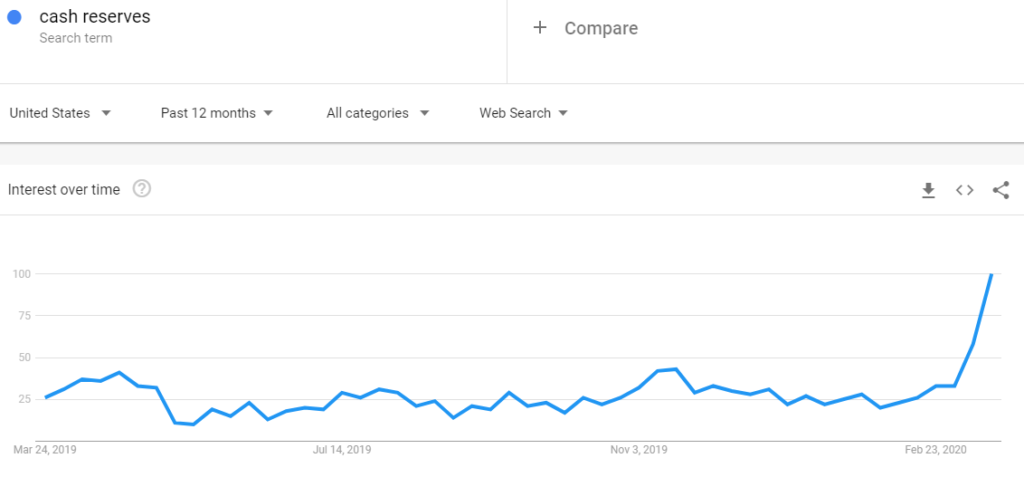

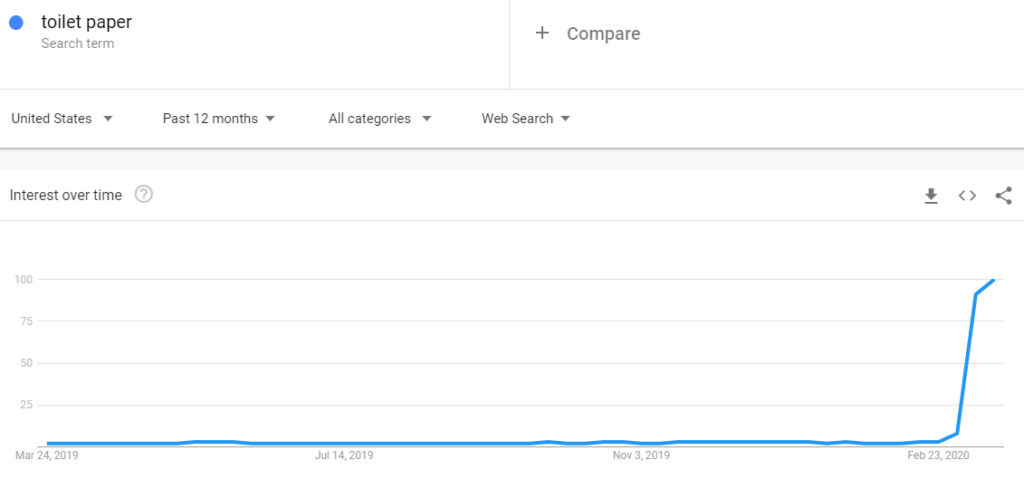

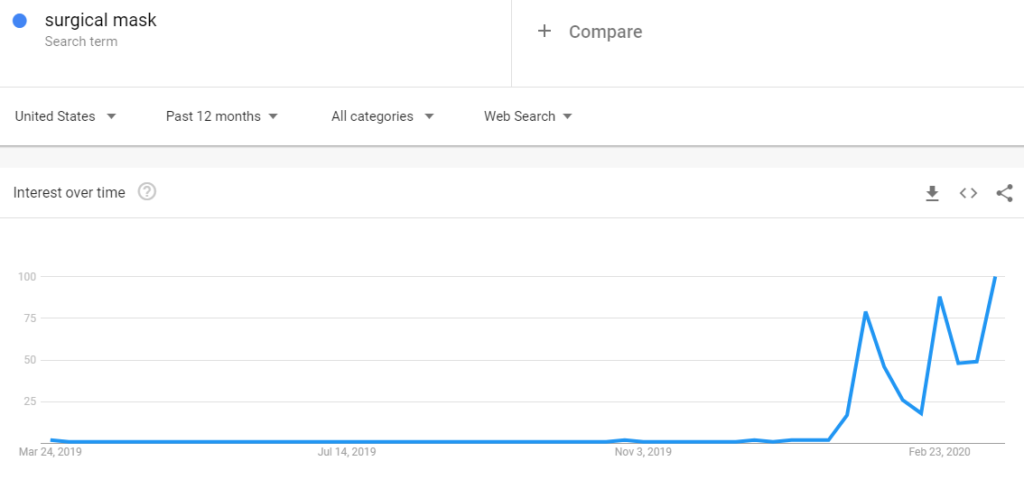

Proof of that cynicism in real-time can be seen below.

Coronavirus: A Clear Case of Overreaction.

We clearly overreacted, too. And knowing where we were before overreacting is just as important as to where we are currently to really understand it.

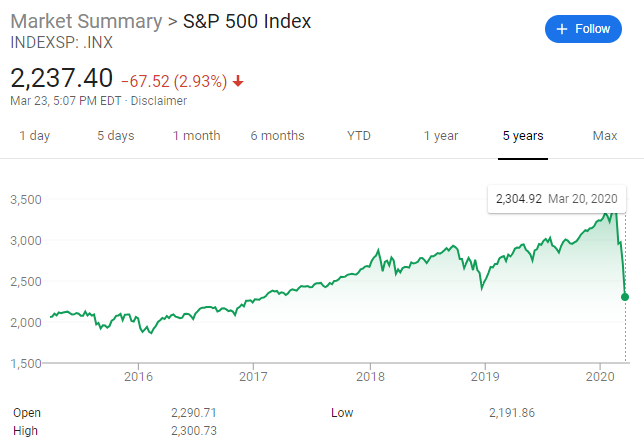

In the US (sorry, I know this is a global problem, I just don’t have a worldly view), we’ve had over a decade of prosperity. Housing and stocks were way up; joblessness and interest rates were way down. When all is good, comfort sets in and complacency results. Economic booms, ironically, set the scene for economic bust (the opposite is also true) and we might have got caught in excess. By we, I mean me, you, our companies, our government, our social norms.

A decade is a long time to forget the pains of our last economic dip and the principles of ultra-savers dissipate. When you’re way up, like we were just a couple of weeks ago, it’s easy to accept waste. We were past the point of thinking through just needs/wants. We had moved past historical perspectives of “do I need this one thing or not” to justifying buying the bundle. Almost always, bundle buying is signaling our acceptance of waste. All the SUVs, cable packages, and the fries with our burger remind us of the bundled consumers we’ve become.

Waste adds to our susceptibility, both in our physical and mental capacity, to deal with change. When the tide turns, as is did in an instant, we’re left fragile.

What’s the knee jerk response to an instant threat? Human behavior kicks in again, and we overreact. We break Newton’s 3rd law and react in a way greater than the harm headed our way.

In hindsight, we regret our mistakes. We might dwell on the opportunity cost. At that point, we’re able to see the bottom and realize it doesn’t match up with truths. In the moment, though, it all seems completely rational to act overly irrational. It might even feel good, as we do “all that we can to not fail.” We’re a rationalizing creature that prioritizes survival, after all.

It’s all part of a predictable cycle (it’s the timing that’s not predictable). And in each of those cycles, we undershoot or overshoot the true bandwidth. We create greater peaks and valleys.

How do we not see it all in the moment and act accordingly? We, as pattern-seeking creatures, look to the past to make sense of the present and predict what’s right around the corner. And as forecasters, we’re not great when we’re in predictable times. In highly volatile times with unknowns everywhere, we stink.

Forecasting is a game of pin the tail on the donkey. We think we have an idea where the donkey poster is hung, but in the act we’re really just fools taking stabs into the dark. The best of us probably lead with the hand without the pin, trying to gather information about our current situation to manage first. Then we update our beliefs and recalculate our approach. Sure, someone will hit the bullseye, but they will be the statistical outlier. Betting on targeting that ass’s ass is a fool’s wager.

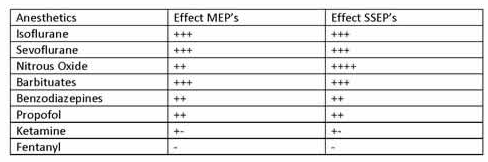

And that’s why you get that pit in your stomach every twist of the Sevo canister. Every rotation is like another spin before placing the tail on the donkey. It’s an unpredictable variable adding to your uncertainty.

So, when running tcMEP, we push for TIVA. We push because we’re terrible forecasters. Slack, or margin of safety, is a reasonable defense (assuming there are no other medical reasons for the contrary). It allows us to control what we can to better make sense of what we can’t. It works in IONM, or any other area where probabilities are important.

“The three most important words in investing — “margin of safety.” The four most dangerous — “this time is different.”

– Charlie Munger

And there’s plenty of other areas in the OR where our technique can build in a margin of safety, as we optimize for stimulation and recording every single time. We look to give ourselves that reminder and pound it into the head of those training; luck is no strategy to bring to the OR.

So as we go forward, whether it be saving in our emergency fund, paying down corporate debt, or asking anesthesia for TIVA on all tcMEP cases, we look to place a value on a margin of safety. We learn the lessons at the cost of non-savors, by those not thinking about the control that a cushion affords you.

At times of volatility, proof of the underprepared becomes apparent.

Excelente!

Excellent!