What Does Your IONM Resume Say About You?

Let’s break down the neuromonitoring field a little bit here (it will help your IONM resume not suck)…

If you had to guess what percent of the cases your company monitors are spine cases, where would you place your bets?

If you don’t have any insider information, then the safe bet would be to choose 80%, seeing as the Pareto Principle has a pretty good track record.

And that’s probably not far off from reality.

Of that 80% of cases, my next guess would be about 95% of the IONM community can monitor those cases (the biggest chunk of the missing 5% are in-house groups using their EEG staff to monitor the carotid endarterectomy cases, which seems to be a diminishing trend).

The percentage of surgical neurophysiologists that can monitor the remaining 20% of cases is a little harder to nail down. My best guess is that around 50% can do some portion of the remaining 20% of cases and about 20% are able to do most.

If those assumptions are close, then about 95% of IONM resumes of experienced neuromonitoring technicians will contain similar content around being able to monitor spine cases and the modalities needed to do so. And about 1 in 2 will have the “something special” covered.

If you’re following the practical advice to keep your neuromonitoring resume to a single page and make use of white space, there isn’t a whole lot of room left to differentiate yourself (on paper, at least).

A Conversation On Contrast

Scott from IONM4Life recorded one of our conversations on a podcast going into some details about the importance of niches, adaptability, and value.

And also eyeballs.

If you haven’t already, my suggestion is to listen to the episode before continuing through the remainder of the article. It helps set things up as this article is a continuation of my thoughts we didn’t cover.

The rest of the article will build on this thought of looking for big ideas shown to survive over time.

Achievement and Contrast

If you’re in agreement with my assumptions above and the points made on the podcast, you might better understand the job of your IONM resume.

Yes, it needs to have what’s expected: name, contact info, education, and past positions.

Yes, it needs to be a succinct snapshot.

Yes, it needs to spell out what you can do.

That’s what gets you past the “no” pile and into the “maybe” pile.

But we’re talking about improving your odds. We want to be in the “yes” pile.

The really heavy lifting comes from achievement and contrast.

Achievements are proof that you’re capable. It fills the same role as real estate agents staging a home. It lets the buyer see that this is a home they can live in (or a person to do the job). It validates the person can fill the job to be done — or more.

They’re also harder to fake.

Achievements require both opportunity and execution. You don’t get them by coasting; action is a requirement. Every hiring manager would love to test you out in the OR before giving you an offer. Achievements act as a proxy for what they’d really like to know. As such, it’s something you should continuously be looking to gain throughout your career. For most of us, it means the ongoing raising of our hand.

The second requirement, contrast, is made up on the margin. It’s what someone (including any references) is most likely to say about you.

Even if you can do all cases and all modalities, 95% of the field can do 80% of what’s available. Well, that’s boring to talk about. To better define someone, we tend to discuss how they’re different more so than they’re the same. Most find it less amazing that we are about 95-98% similar to chimpanzees (the bulk of everything) than the fact they have superior short-term memory than we do (one comparison).

Why would discussing you be any different? We overweigh our differences.

So while earning the CNIM is a great achievement for any surgical neurophysiologist, it might not have the contrast you’re looking for, seeing how it’s a luxury item and all. It’s a hurdle to get past but not something different enough to label you by.

It’s the fringe that better defines us, seeing as we can all look very similar on paper. And it’s the fringe, or borders, that we’ll use to guide us in our plans to achieve things that matter and differentiates us from others.

Assessing Opportunities and Threats for Achievements and Contrast

We’ve already covered how we have blindspots because the brain favors efficiency for sustainability, but we can see this in other aspects of adaptation in nature.

These are considered nature’s invisible force. But all that we see and experience is stitched by invisible threads of forces in geometry. Knowing this can help make the invisible visible.

Voronoi patterns, for example, favor efficiency by assessing a seed (node) point to its nearest neighbor, shortest path, and the tightest fit. No other seed is closer to what’s inside that cell and there are lines halfway to neighboring seeds.

You can see these geometric patterns in the giraffe’s fur, dragon’s wings, and turtle’s shells.

Interesting, sure. But what’s this got to do with us?

THERE ARE INVISIBLE FORCES DETERMINING YOUR FUTURE!

If we can make the illegible legible, we can better plan for ourselves. And taking time-tested frameworks repeated in biology gives us confidence in their utility if we can adapt them right.

Our lives, however, are moving targets. We want to model something that introduces change, like new employees, new goals, new company challenges, and new life seasons. We’re also parts of different systems of varying sizes (individual, team, organization, industry, category, etc.), and would be wise to consider different levels.

The Organization

Using Voronoi patterns is helpful in deciding where to dump toxic waste or where to build a hospital because it mimics nature’s ability to prioritize sustainability. Company owners and/or CEOs might use this model (stripped of all the math) from a top-down viewpoint, too. They might be trying to better answer questions about what positions I need to hire for, who is currently best situated to handle a task, or whether is there an area where output should be greater. They would start by looking at the organization, or a section of it, before the individual cells.

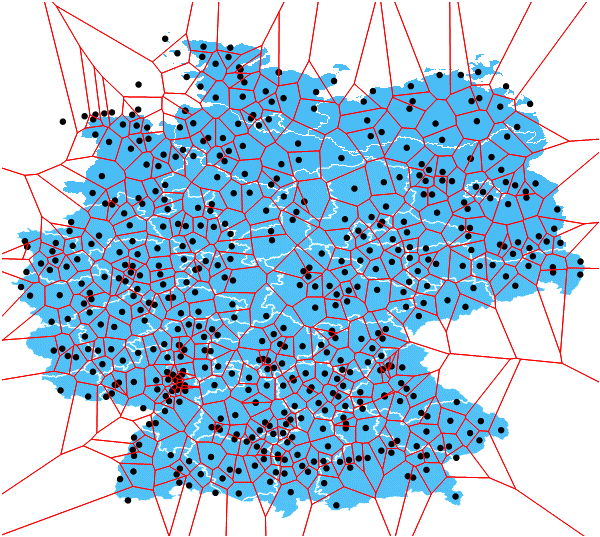

To them, with all the moving parts, they might have a 10,000-foot viewpoint like this:

That might be overwhelming if it’s your first time trying to orchestrate all these nodes in a network with an overarching goal of growth and sustainability.

It also might help us appreciate the ease with which one might “get overlooked” or “not appreciated” in this jumbled mess. That perspective lends leniency to the person AND highlights it is up to us to stick out in a good way.

The Individual in the Organization

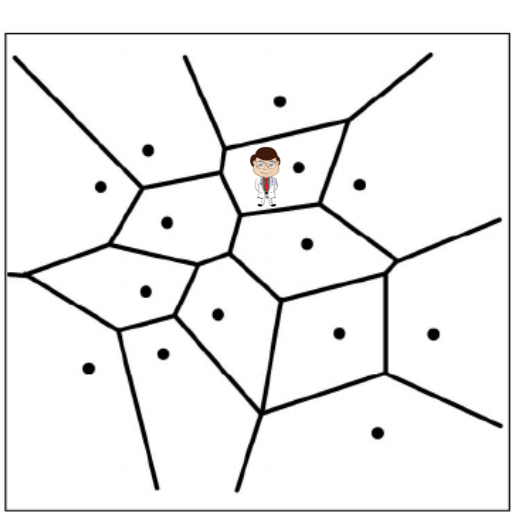

To help determine our ability to gain achievements and earn contrast, we might be better suited to zoom in on our more immediate surroundings.

If you can imagine yourself and what you do for your organization encapsulated in some always-changing, ill-defined cluster of responsibilities with irregularly-shaped borders, linked with everyone else in your organization, then you might find this exercise useful.

Your seed, for reference, is pretty much what’s on your job description (the middle). It’s what you do day in and day out. Your fringe or borders are what butts up against opportunities outside of the norm. Your cell shape and volume are dependent on both how much and the type of work you do compared to others in that organization.

Our intention is to gain opportunities on which to execute. You want to focus on your cell first and move out from there, depending on the direction you wish to take and the opportunities present or possible.

Now, one can change all the cells all at once by adding another seed, which we all hope to happen as our companies grow with prosperity. If it is a neighboring seed, you might see drastic changes in your responsibility. A new hire that is new-to-the field might mean what your day-to-day looked like might change. It could mean less overtime, fewer spine cases, more training, etc. If the new hire was distant to you, like a new billing supervisor, your cell’s shape will be minimally affected (assuming you’re not looking to get into billing).

Think of ripple effects, here.

And so you can see your neighbors that matter more. Knowing this, we might want to zoom in again on our cell and draw out an honest representation of our cell volume, borders, and the interplay with our neighbors.

The Individual in Close Teams

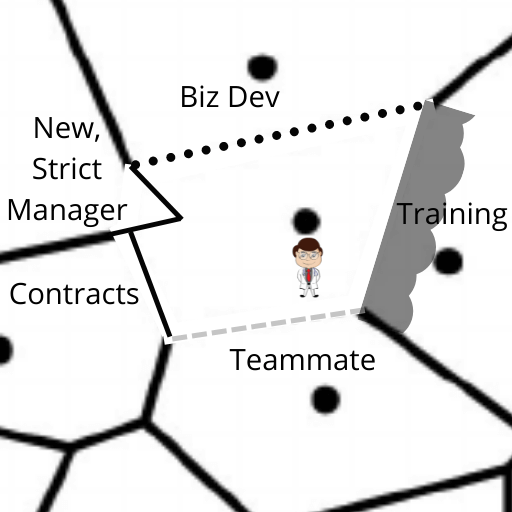

Let’s take an example:

Here’s the story that would go along with this image:

Last month, you had a change in your manager. They are still getting their bearings in their new role, but so far they are micromanaging, took over some of your responsibilities, and have yet to start 1:1 meetings. The border you sketch would be a solid hard line encroaching on your space. It’s reducing your total responsibility volume. On the other hand, you had a conversation with business development to see if you could help them gain some more local business. You haven’t acted on it yet, but they are open to collaborating, so it is a dashed line. What you really want to do is more work as a clinical trainer. You like it and like helping others. You have a translucent border that encroaches on another clinical trainer’s cell as you’ve been taking on those responsibilities. At the current moment, that seems to be the path of least resistance. You’re lucky that you’re part of a strong, helpful team, so that is a dashed translucent border, too. You got their back and they have yours, but the ability to get contrast there might be harder to find. Contracts are not something you deal with or care about. You’ve never even seen one. But because they are working so much with the new manager and business development, their position went from distant to a neighbor, though the border is small.

Here you can see there are 2 opportunities present: business development and clinical training. There is also the threat of encroachment and solid border from the new manager.

These observations are all part of your own career management and should help determine the conversations you have and behaviors you take to nudge your career in the direction you chose.

Your Catalyst For Change: The 10% Rule

You’ve probably heard companies like Google and 3M allow time for their employees (or at least the ones creating things) to work on something not assigned to them. It’s a time to “play” with ideas, collaborate with others, and push the boundaries of what’s currently part of the company’s business strategies.

This was part of their job description: “to make Google better.”

You, most likely, do not have that written into your job description. More than likely, it never will. On a pay-for-service model, it’s not so easy to justify. And our non-traditional daily routines of variable times and durations make anything concrete like that even more difficult to enact.

But you should, anyways.

Outside of the summer and end-of-the-year rush, we can usually find about 10% of our time as idle time.

It won’t be every day. If today you’re doing 3 flip rooms at a surgery center, but know you’re working at a teaching hospital the next day, you can plan accordingly. Hey, maybe you even get Friday off to carve out some serious blocks of time!

Wait, Your Suggestion Is To Work More?

Kind of, I guess. It’s what you prioritized as essential opportunities or threats to address.

What I’m really suggesting is to be purposeful and efficient with your time to find that 10%. I’m not telling you to give up your nights and weekends (unless your goals are lofty, like earning another degree), but squeeze in production in the direction of your choice during downtime.

The nature of our time requires travel and wait time at the hospital. Those are the minutes I’m suggesting you use to fill up that 10%.

If you’re going to be working a big chunk of your life — like most of us will — there’s too much upside to let the thought of burning a couple more calories deter you.

Plus, what you’re targeting are things that give you energy. Things where your curiosity pushes you to find answers.

Work on things that:

- interest you

- provides value to your company, making you more valuable (and increasing your sense of self-worth at your job)

- provides value to future you (like what was mentioned in the podcast)

- provides contrast on your resume, making you a safer bet with asymmetrical upside

Building your IONM resume isn’t about enabling job hopping, though it helps there too until you do it too much. This isn’t my stab-you-in-the-back document.

An IONM resume is about keeping track of what you’ve done and better think about where you’d like to go. It’s about keeping your career top of mind a couple of times a year so you can purposely nudge it in the direction you hope to go.

Here’s how I suggest going about your IONM resume upkeep:

Step #1: Discuss plans with your supervisor.

Google and 3M outright gave permission to “go hunting and let’s see what you come back with.”

For them, that resulted in Post-It notes, Google Adsense, and Gmail. All monster successes.

Some of you might already have these conversations with your managers. Congratulations to both of you. Others might need to create a 10% plan and pave the way.

In these discussions, it’s critical to discuss your interest, how this provides value to the company, and how you intend to accomplish it.

Use the powerful framework of what, why, and how. 10% of the conversation is what you want to do. 70% of the conversation is why. 20% is how.

Notice how much time is spent on the “why.” This is the section that deals with emotional thinking and subjectivity, which is the context of the facts laid out on the bookends.

There might be some tinkering with the plans or reworking of the goals, but what you’re ultimately looking for is to take your manager along for the ride.

That’s right, you don’t want them to just say “OK.” You want them to be committed to this thing by providing you feedback, recommending resources or mentors, and maybe even helping clear a path.

And that takes time and effort. So you’ll really need to make sure the way you handle this helps them and the company in the most frictionless way possible.

We’ll accomplish this in the last step. But first…

Step #2: Consider neighboring roles

Looking to craft your ideal career, you should consider how this 10% can affect others in your organization.

Sure, you want to think about this because it will affect their work.

But there’s something else to consider when you’re looking to gain accomplishments and contrast. (And here’s the big secret question to ask)

Ask yourself… what would they do differently when tackling this objective?

This hack will better protect your thoughts from fixation, where you’ll inevitably fall back on ideas already thought of. It works better than other suggestions, like letting your mind wander or going to sleep thinking about the problem.

Changing perspectives from yours to the other roles in your company (or customers) allows you to see from different angles or better deal with any blind spots.

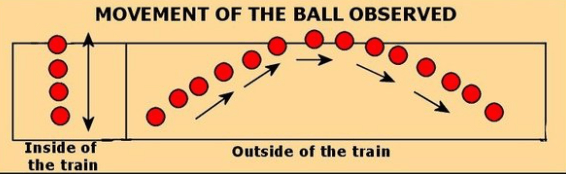

Like the classic example goes, what does the movement of a baseball look like to the person on the train throwing it up in the air and catching it versus the onlooker outside of the train?

This new perspective might help you accomplish your objective that encourages future collaboration with your organizational neighbors, as well as do it in a way with a higher likelihood of success.

Step #3: Lay out the roadmap.

This is where you present the first attempt at figuring out how to accomplish this 10% goal.

And you’ll want to do this by bringing in something that is so foreign to the neuromonitoring space it might even seem crazy to suggest.

Create rhythm.

Surgical neurophysiologists live in the moment of now. We have very, very loosely planned weeks because we could always be wanted now.

When can you be here? (The only answer is now)

When can you get baselines? (The only answer is now)

When did you see changes? (The only answer is now)

We are always on now’s time. Future planning using calendars is what most workers consider must-haves. It’s not really mentioned much in our field.

But this is where you break out of that norm and establish a rhythm.

You’ll want to carve out time on your 1:1s with your manager (maybe once a month?) to discuss your 10% progress, hangups, deliverables, and feedback. Put it on the calendar.

You’ll want to set deadlines for yourself (and anyone else involved) to hold yourself accountable.

This can easily be done by using a calendar and task. If there are a lot of moving parts or people involved, I suggest using something like ClickUp to help organize the process and provide a place for asynchronous communication.

Chunking things into 5-day deliverables helps ensure this isn’t something that falls off a cliff, only to be dug up when you’re talking about annual goals for next year with your manager.

Create a rhythm to create habits to create accountability to better guarantee success.

Step #4: Measure and document everything.

Now that you have a plan designed, make metrics to see how you perform and track it over time in your IONM resume.

This will do a couple of things for you.

- Allow you to keep your rhythm. You’re looking to create habits here. Not just yours (doing the work), but your managers too (getting the feedback and recognition). Keep good records and plan on having discussions on your 1:1.

- Keep track of not just what you’re measuring, but the lessons learned, successes and failures, and the context behind them. You’ll need these stories to bring to life the achievement and contrast from your resume.

- Do a quarterly wordsmithing in your master IONM resume. Here you will continue to add achievements and points of contrast to an evergrowing list. Write them in ready-to-be-used form. If/when you look for a new role in or out of your current company, you’ll be able to cherry-pick those best suited for the role you’re applying for. You’ll want to have dug your well before you’re thirsty.

Finishing Up The Example

In our example, the ultimate goal was to do more clinical training. In most companies, it’s a competitive position to go for, because it’s rewarding, fun, and valuable. So we’re going to use our understanding of our Voronoi drawing (probably should spend some time at the organization level, maybe some other key people like your manager and the head of training) plus our 3-step action items to get a plan in action.

We already analyzed our threats and opportunities (think through your strengths and weaknesses to complete the SWOT analysis). So we want to do something that moves us in the direction of the clinical trainer, that helps break down any barriers to communication and trust with our new, strict manager, and allows for future collaboration with our neighbors to gain experience, perspective, and achievements in areas that will make us stick out in a good way by assessing the objective through the lenses of different roles in the company. We then future plan it by breaking it up into 5-day chunks of deliverables defining who does what by when. That all gets measured and recorded.

The approach might look something like this:

- Create a 15-20 minute presentation on the novel neuromonitoring technique of nerve monitoring-guided selective hypoglossal nerve stimulation in obstructive sleep apnea patients.

- Create an accompanying cheat sheet for the clinicians to take home with them to study up before they get trained on it.

- Create a 1 sheet surgeon brochure highlighting the benefits of nerve monitoring in these cases to discuss with the business development team.

- Create a roadmap to discuss with your manager what it might look like to help business development get new business in their market + train their team to cover those cases. Include the manager in the plans to discuss with business development and the education team (assuming there are roles for those at your company).

- Create a cadence for ongoing discussion with your manager around this initiative.

- Collect useful information to add to your IONM resume bank (# of cases added, Revenue added, # of clinicians trained, surgeon satisfaction scores, close rates, etc).

- Collect stories to accompany the achievements of the initiative.

Then write up an attractive bullet point for your IONM resume bank. It might look something like this:

- Created surgeon targeting and clinical training for untapped surgical cases leading to an additional 177 cases per year.

If I was a manager interviewing this candidate (who most likely would have the responsibility for cases performed and clinician proficiencies) a question I’d be dying to ask would be:

“How did you do that?”

If your response demonstrates initiative, creativity, collaboration, and execution, I’ve got other ideas floating around in my head on how you might fill a void and fit on my team.

That’s because achievement and contrast will dominate my mind space, even though it has little to do with 90% of the surgical neurophysiologist role I’m hiring for (which is to do case coverage consisting of 80-100% spine).

Your IONM Resume Is A Living Document Of Persuasion

Just like making a purchase, hiring someone is far from acting with complete rationale. There’s more to it than the objective ranking of a school, completion of degrees or certifications, and years of experience.

Understanding hidden forces of opportunity and emotionally driven decision-making is part of understanding the rules of the hiring and promotions game being played. Hopefully, this helps you play it well over a career you helped shape.

Great read! Novel and effective blueprint for professionals in our field to pursue ideas and land our own “10 percent” moments.