The surgeon uses navigation and wants to know why she should use motor mapping for her crani?

That’s the question posed to me by a clinician years ago.

It was just before I set up my case and they recruited me into the conversation. So I walked over to the room next to mine and held a 20-second conversation to demonstrate the value of mapping. It was with a surgeon, so that’s about all you’re going to get.

I started the conversation with the exact title of this post: “It’s Not Navigation Vs Neuromonitoring; It’s Navigation And Neuromonitoring.” I probably won some persuasion points by being one of the first reps she ever heard not immediately try to oust a competitor, but I think I made a strong case by keeping it simple and direct.

Not my strong suit.

Afterward, I figured it would make for a good topic to discuss, so I made a presentation to give at one of our monthly company-wide training sessions. It was very much a technical talk to help clinicians improve their technique, troubleshooting, and interpretation.

Or at least that’s what the title page said…

The topic was definitely about how to “improve their technique, troubleshooting, and interpretation” during motor mapping cases, but it wasn’t accurate to say that it was “to help clinicians improve.” It had 75 content-rich slides for a 50-minute talk, so you know exactly how that went.

Oh, cool. Joe’s giving a crani talk today…

It was exactly the opposite of what worked with the surgeon.

Now, I spent a lot of time on it and did a pretty good job of reviewing the literature and incorporating my own experience. Still, it didn’t hit the target.

And there’s a simple reason for it: I missed the intended audience for the presentation.

I may have started out creating a presentation for my colleagues to help move the clinician/company/profession forward, but that’s not where it ended up. The presentation ended up all about me. Set up to show how much I knew, it excluded the listener’s reason for attending as a factor.

And those incentives changed the outcome of hitting my goal: correct information empowering other clinicians to discuss, understand, and perform mapping during craniotomies.

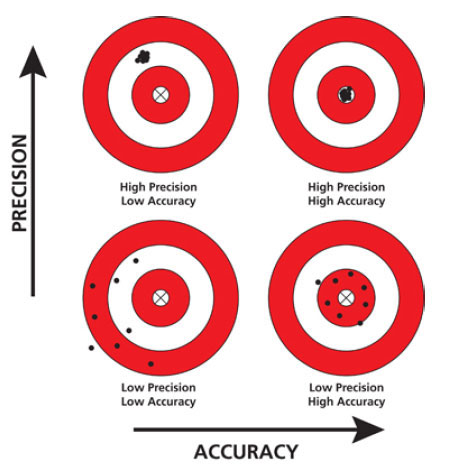

The content was precise in that it was repeatedly correct, but the accuracy was off in trying to make an impact across different levels of familiarity with the case type and modalities.

When considering how my lecture lent itself to transferring information in a useful manner, my target looked like the upper left: clustered together and off to the side. Given over and over, the information would hit the same mark. It was a review of the literature and repeatable best practices.

Unpacked as a scatted review of the literature — without any progression or story arch — rich with jargon and void of compressing the information into simple, consumable chunks, it muddied connecting any dots. It missed in fulfilling the job to be done: train the next group of SNPs to provide IONM services during a craniotomy. I’m sure people picked up bits and pieces as I sometimes hit the mark, but only for brief moments of coherence.

It lacked accuracy.

Accuracy, in comparison, is getting close to the true value. It would have to be closely agreeable to an acceptable standard (as in, this is how you present to allow people to actually learn). It’s a degree of veracity; it targets the bullseye. Had I remembered who was the primary beneficiary of the lecture, the target would look closer to the upper right target. Both accurate and precise.

The Presentation: Motor Mapping

For some context, here are a couple of slides from the presentation. Notice the first 2 slides are both accurate and precise — and then the wheels fall off.

As far as what someone might retain and use, the slides have a downward progression and decline in accuracy.

Precision and Accuracy

Now, here’s why I’m telling this story of Precision and Accuracy within my motor mapping talk:

- It was accuracy, not precision, that helped me win over the surgeon during our conversation. Always optimize for accuracy first, then concentrate on precision. I lost sight of that when I created my presentation.

- The second part of my discussion with the surgeon — the part where I made my point — covered accuracy vs precision... because that’s the discussion of Navigation vs Motor Mapping. It’s a story of strengths, weaknesses, and complementary technologies.

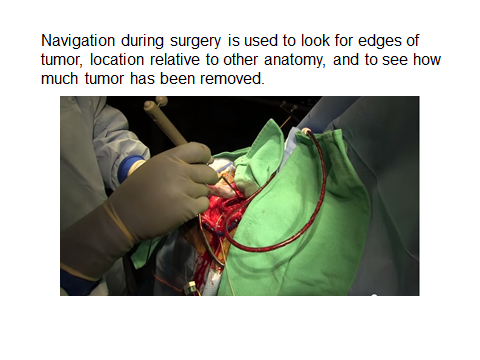

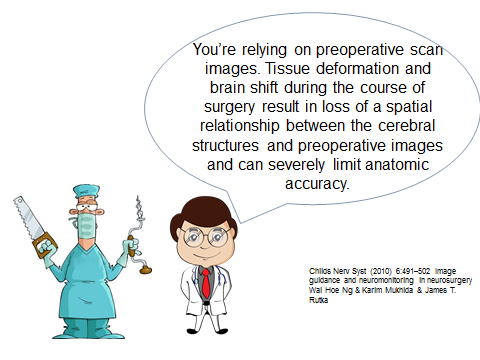

Now, go ahead and reread the slides above (slower this time) and you can see where disruption occurs in Navigation’s accuracy. Pre-operative static scans cannot accurately represent the current positioning after different types of shifts happen. The coordinances are off and the map is no longer the territory.

OK, so what about motor mapping?

There’s a general guideline from some previous research showing repeatability of changing the distance of your stimulation to the CST by 1 mm will positively correlate with a change of 1 mA output. If your CMAP is at 3 mA, you’re 3 mm from the white matter. A little tumor debunking happens and if the CMAP is now present at 2 mA, you’re 2 mm from the white matter. It repeats, so it is precise. It doesn’t matter if there is a shift during the case (debunking tumor, drain cyst, etc.), it is also accurate.

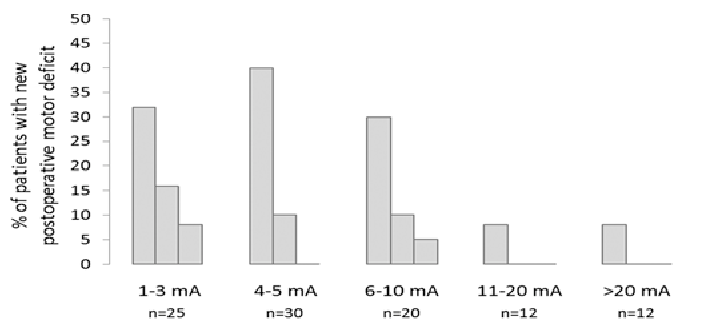

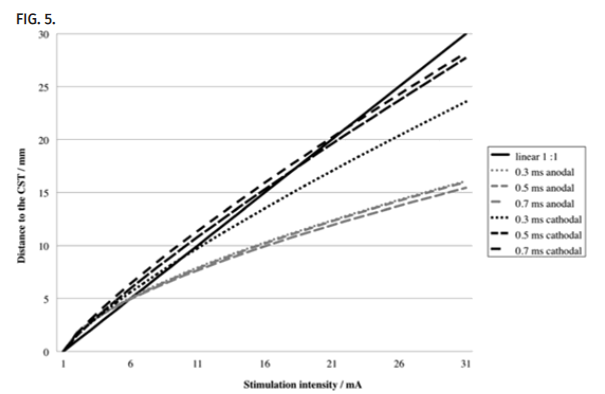

But motor mapping has an interpretation of the precision problem of its own: the replicating output to distance change does not follow this 1:1 rule forever. If you take a look at the image below, the solid black line would depict and ongoing 1:1 ratio. That is a purely linear line and would represent precision and accuracy. You can see things fall apart around the 6-10 mA range for some stimulating techniques.

And this makes a difference when we’re discussing strengths and weaknesses with our surgeons. We must accept the nonlinearity of the threshold curve and know how to make appropriate suggestions given the constraints. Here’s an example:

There is a nonlinear correlation between stimulation current and the distance to the CST; thus one is approaching the CST sooner than expected following a linear correlation pattern, as reported frequently in the past. Therefore, subcortical stimulation should be used more frequently during tumor resection close to the CST.

And this makes a difference when we’re discussing strengths and weaknesses with our surgeons. We must accept the nonlinearity of the threshold curve after optimizing as best we can (see the above chart again) and know when to act accordingly. As we better understand what we can and cannot offer, we become more accurate in our suggestions.

As accuracy improves, we can then expand the service we previously provided. We can give better estimates of confidence, allowing medical opinions a closer approximation to truths.

Here’s a beautiful example:

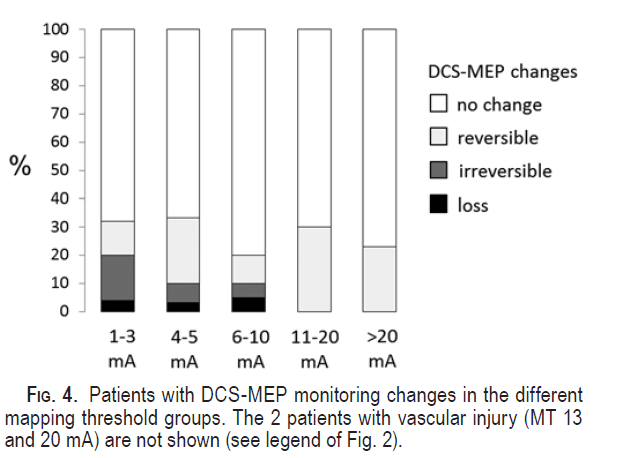

As described by Seidel, et. al., mapping thresholds (as described above) used in tandem with direct transcranial motor evoked potentials correlate with the risk of injury. While direct transcranial motor evoked potentials are a better predictor of a post-op deficit, it is not always reversible (only 60% of cases in their study). That makes mapping with motor thresholds not only helpful for determining distance but also understanding the probability of injury before it happens. Depending on what type of tumor you’re working with, the surgeon can better do a risk assessment (need to get this tumor out of there vs. play it cautious and monitor). It also helps temper expectations of deficits after immediately arising from surgery. In some of these really bad tumors, success might actually be defined as 100% tumor removal with temporary weakness an acceptable tradeoff.

Conclusion

If you have to choose, choose accuracy. But remember, this is brain surgery we’re a part of, and both precision and accuracy matter. And as a result, it’s up to you to not only better understand the craft of neuromonitoring, but also applying concepts broadly. Understanding the difference of accuracy and precision, what to prioritize, and how to pursue improvement in either or both makes you a better decision-maker and a valued part of the surgical team.

Couldn’t agree more, especially after listening to Jeremy Banford’s recent ASNM webinar on mapping the human homunculus. I disagreed with his methodology of relying so much on determining tri-phasic SSEP patterns being adjacent to critical motor area/pathways. I would rather take all that time to more precisely map motor function using the Taniguchi technique of multi-pulse stimulation. And he didn’t even talk about one of most crucial new developments in using a surgeon controlled probe coupled with suction to greatly reduce false negatives encountered due to current shunting.