It’s easy to see that COVID-19 caused a neuromonitoring training problem, but did you know we have a chicken sexer problem too?

I owe you an explanation for that one. But before I explain myself, let me tie it into some of my past post.

In a couple of recent articles, I’ve made the point in intraoperative neuromonitoring training and job growth, different is better than better. Bringing something valuable and scarce to your customers and your company is your edge.

And I still hold that as true.

But I hope the need for being really, really good at the craft of IONM — dedicating yourself over long stretches of time — doesn’t get lost on you.

While the gap is not so wide we all can see flashing red lights, the need/gap for those clinicians continues to expand. These beholden SNPs — the ones who put in the work and made the most of their time to accumulate experience — going forward will be referred to as chicken sexers.

Chicken sexing is a little known profession reliant on instruction and immediate feedback from a master sexer to train apprentice sexers in the art of making accurate, split-second decisions.

And since that’s such a useful skill for a top surgical neurophysiologist, especially at a time where social norms are at odds with developing it, we’ll see what we can learn from them.

Borrowing Neuromonitoring Training Techniques From Master Chicken Sexers

This chicken sexer job (kind of gross in my opinion) is where you sit down and do nothing but look at baby chick genitals. The reason is the value of female chickens over males — you know, for the better meat and egg production. Properly sorting these baby chicks is valuable for the farm owners. The job actually pays pretty well.

Remember, it pays to be scarce and valuable.

In baby chicks, it isn’t cut and dry when identifying a boy or girl chick. You’re just looking at a bump vs. a slightly different bump.

It’s so subtle, that it’s even hard for master chicken sexers to tell you why it’s one over the other. Yet they rip through a pile of chicks in no time. It takes less than a second to check under the hood and put the chick in the male or female pile.

And they do it with almost flawless accuracy.

To get good at chicken sexing, there are 2 main criteria.

- You have to be right.

- You have to be fast.

Doesn’t that sound familiar?

I don’t mean to marginalize what we do, but from a 10,000-foot view, being right and being fast is a pretty good yardstick to rank performance for surgical neurophysiologist. If there’s a problem in the OR, you’re required to troubleshoot, give differentials, give probabilities, and give suggested interventions without delay. It’s a priority of any well thought out neuromonitoring training program.

Here’s the rub: accuracy and speed, most of the time, are at odds with each other.

Our big brains, evolving over millions of years, are well adapted to sacrifice accuracy for speed. We fill in gaps, or blind spots, to change our perception of the world around us.

Historically, that’s paid off. If you see a skinny brown thing out of the corner of your eye, your brain tells your eyes to dilate, your heart to pump blood to your limbs, and your legs to jump in the other direction. That’s a much better survival process than taking the time to decipher between a snake and a stick.

Our brains developed not to worry so much about false positives (or type I errors). Or said differently, we evolved to not prioritize accuracy.

The risk is just too great.

Instead, seeking to understand and remember familiar patterns allows us to prioritize speed.

But these chicken sexers are able to do both — with something like 99.9% accuracy.

And that’s the magic we’re in search of incorporating into our neuromonitoring training. While we’d rather tilt towards a tendency of false positives than false negatives — in surgery and in life — we still strive for accuracy.

The problem is, in my opinion, we’re swimming against the current. And before we can fix the problem, we need to identify any root causes.

The Rise And Fall Of Chicken Sexers In Neuromonitoring Training

The field started off with professionals adopting neurodiagnostic techniques into the operating room; BAER, SSEP, EMG, H-Reflex, and EEG to start. There was, of course, a lot of trial and error. With limitations in communication, discoveries and mistakes were made in parallel.

Fast-forward to a more established profession, clinicians now had a solid foundation to help train others in a systematic manner. Those clinicians would ultimately be out on their own, although cell phones and IM chat progressed along the same timeline to make real-time communication easier. Second opinions were now available during the case.

Then the on-sight and remote physician oversight became an established standard (at least it did in the US). This guaranteed real-time communication for each case monitored. As such, worlds began to collide and dual mentorships formed. Clinicians got rapid feedback on medical opinions. Physicians got rapid feedback on technical opinions. Both sides could learn from the other’s strengths. The feedback was immediate.

Over time, this makes for better clinicians in the room and physicians off-site. Information turns to knowledge and knowledge turns to wisdom. And it is at this point intuition *might* become valuable.

But with the neuromonitoring profession using new technology to better sharpen old hardware (our brains), it allowed for cheaper and easier communication (because that’s what the deflationary forces of technology do). As a result, globalization took another giant leap forward, optionality increased, and workers were no longer locked into working locally or in a specific career they chose early in life.

Millennials, known as super smart and super mobile, found it easier to find the next thing. Careers, as well as a lot of life, was no longer set to a linear timeline, but rather as separate projects, sprints, or experiences.

A shift of breadth over depth comes with all new innovations at the expense of mastery. While both are desirable, this writeup highlights success found through practice over time, the pursuit of reclaiming accuracy along with speed, and the problems ahead posing as a threat.

Problem #1: Who’s Putting In The Reps?

A problem not isolated to neuromonitoring: workers are job hoppers.

And it’s not just jumping from one company to the next, it’s jumping from career to career. If you’re in the position to do interviews, you’ve seen the diversity of job history applying for positions. It’s all over the board. Long gone are the days of audiologist and EEG techs making up the resumes for neuromonitoring training programs.

On the way out of the field… that’s a little less clear to me. Not because it’s hard to find out; it just takes some leg work on LinkedIn to find out who is now a MD, massage therapist, real estate agent, engineer, or politician. It’s just a less fruitful practice.

When considering neuromonitoring training, it does beg the question: what emphasis is being placed on mastery?

It seems not much. The above graph is shocking simply due to the short duration. It usually takes about 18 months, on average (almost never trust averages, btw), to become proficient at a job.

Sure, it’s easier if you’re hopping to the same job with a different company, but there is still change you’ll need to adapt to.

For me, it’s just really surprising.

All except for the first two groups — I completely agree with them. When you’re young, explore different areas. You’re still looking to decide what interests you, what shows promise, and where you see a path to the future you want. In that age group, exploration is typically the way to go.

But as you get more seasoned, the advice typically swings from exploration to exploitation. As you gain mastery, your ability to produce (and as a result, earn) is greater.

It makes sense to hang out by the fruit-baring tree.

But the standard “explore and exploit” advice requires the right context. 20 years ago, valuing security and placing faith in meritocracy tilts you towards exploitation. Today’s workforce values growth and autonomy, or over-weighing exploration.

For employers, like it or not, the mobile workforce fills the pool of applicants. Portfolios (highlighting production) replaces resumes (highlighting time horizons). Generalist replaces specialists. Pipeline replaces job postings.

Problem #2: Who’s Giving Feedback?

There’s a problem coming up in the nursing field, which parallels IONM. We have a large population of retiring professionals — the ones with all the years experience of doing and training.

The difference is this: while both professions have a job-hopping, mobile workforce, the nursing profession suffers from a supply shortage as well.

IONM’s apprenticeship model keeps the new-to-the-field pipeline full. It also leaves us more susceptible to problems with proper training for new entrants.

As both professions are left with the ongoing question of “who’s up next?”, the loss of wisdom causes regression in training programs. Of course, there’s plenty of new learning platforms to help store, consolidate, and curate information, but here it is the lack of feedback in the moment from experienced clinicians at risk.

And that’s probably a bigger deal than you’d expect.

Feedback, in the moment of doing and learning, is a powerful tool for shaping our understanding. It can transform us from thinking like a surgical neurophysiologist to being a surgical neurophysiologist.

Thinking like a surgical neurophysiologist comes from textbooks and examples. Being a surgical neurophysiologist comes from guided experiences.

The above article hit home for me in particular, as my wife is a professional with animals, and I work in the operating room. Creating a feedback response, like a click or a whistle, has always worked well to train animals. According to Dr. Levy, it works for medical students as well.

Now, you’re sure to get some stares if you go into the operating room with a little clicker and a pocket full of yum-yums, but you should not disregard the power of feedback and the importance of timing.

Both positive and negative feedback helps rewire our brains in such a way that we better adapt. If we signal to our brains that what we’re doing is important through repetition, it will reward us through synapses. We can further cement or destroy those synapses through positive or negative feedback (especially if immediately given).

It plays little difference in our learning to survive, say hunting, as it does for learning a skill to build a career around. We are pattern recognizing animals and feedback are votes to do more or less of something. As we continue to develop in a specific domain, our brain will start to recognize patterns and fill in the blanks even when imperfect information is given.

It’s how professional hitters subconsciously identify a curve ball, chess masters know the best moves in familiar boards, and top surgical neurophysiologist troubleshoot with just a quick glance.

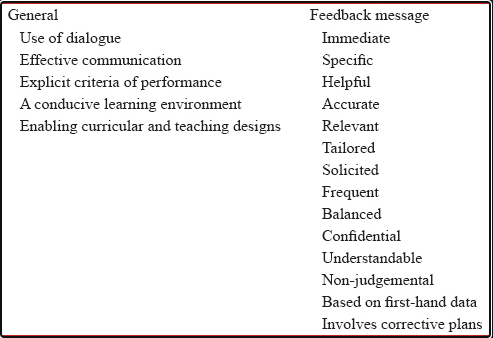

While a clicker is an easy way to communicate yes or no, binary information is just the place to start. Feedback, itself, is a graded response requiring feedback. While master chicken sexers might get away with simple feedback for binary decision making, surgery is an environment of complexity. Training the best surgical neurophysiologist requires more.

Problem #3: Who’s Grading Outcomes?

Someone or some group of people are typically responsible for writing protocols, procedures, and best practices for each company. These are typically leaders of the group.

I’ve already touched on changes seen in neuromonitoring training and job “fit” depending on the state of scarcity vs abundance. This also has impact on the qualities of leaders of a group or an organization.

At times of scarcity, effective leaders were typically charismatic sources of direction. Groups looked to her or him for instruction and best use of limited resources.

In times of abundance, leaders rely less on their own personalities to get people to move one way or another. Instead, leadership places focus on the group to push beyond any individual’s margin of competency while supplying the resources to do so. These leaders win by finding the best in their people.

How Does Democratizing Leadership Affect Neuromonitoring Training?

Both types of leaders require confidence, just expressed differently. Moving from scarcity to abundance means leaders shifting confidence from inward to outward.

Confidence, afterall, is a signal of fitness — important for all leaders. We see confidence as a sign of reassurance in others; someone we can trust.

But confidence without gradation is a dangerous combination. We are better off following leaders expressing concerns as probabilities, even at the expense of our trust. That would require moving outlook from short-term pain to long-term payoff.

Simple, but not easy.

Why, you might ask? Because there’s not much more dangerous than a brilliant execution on an awful idea.

Outside of the handful of truly narcist people you know, misguided confidence is a feature, not a bug. It allows us the ability to act when pattern recognition kicks in, allowing the peace of mind found in familiarity.

Here, we act intuitively.

Because how we experience the world is always off from true reality, intuition is always wrong. But sometimes, it is both wrong and useful. This more commonly happens with intuition in areas of precise familiarity. The problem with the confident people have in their intuitions is that it is not a reliable guide to their validity.

Ask someone with an intuitive sense how they know something and they will likely give you a less than specific answer.

“Because I’ve been doing this for 20 years…”

“I’ve seen it a hundred times before…”

“I just know…”

Not being able to conjure up a reason comes from the fact that much of the pattern recognition is done subconsciously. We are able to use information from scenarios we rarely remember, called priming. This priming allows you to make some leaps of faith, subconsciously and rapidly, to identify the details of one situation coinciding with the details of another.

So for the experienced surgical neurophysiologist, relying on intuition creates a bottleneck in a company’s neuromonitoring training program. It’s hard to pass down experience through decisions made from intuition.

Any Other Issues?

And worse yet… what if they were wrong?

If that’s a shrinking group, then who’s left to help them course correct?

You know… old dogs, new tricks, and all of that.

But this isn’t a case of capability, it is a case of self-preservation. At least, that’s how we are wired to react. Arguing like you’re right and listening like you’re wrong goes counter to our self-narrative. That’s the story you believe about yourself that you will, sometimes unknowingly, fight tooth-and-nail to maintain.

Ungraded thoughts/behaviors risk poor accuracy with potentially high precision. Strong opinions tightly held become well myelinated mistakes over the years.

Not great for pattern seeking, intuitively driven beings.

The problem is intuitive judgments tend to only work with accuracy in areas where feedback is fast and cause and effect clear. While science is an institution built around self-correction, it’s own self-restricting, and necessary, principles makes determining cause and effect difficult in the medical setting.

We can’t just treat people as lab rats.

Neuromonitoring feedback on feedback

The alternative solution, collecting large data sets, takes time, is expensive, is beyond the sophistication of some companies in our space, and is in opposition to incentives of privately held companies.

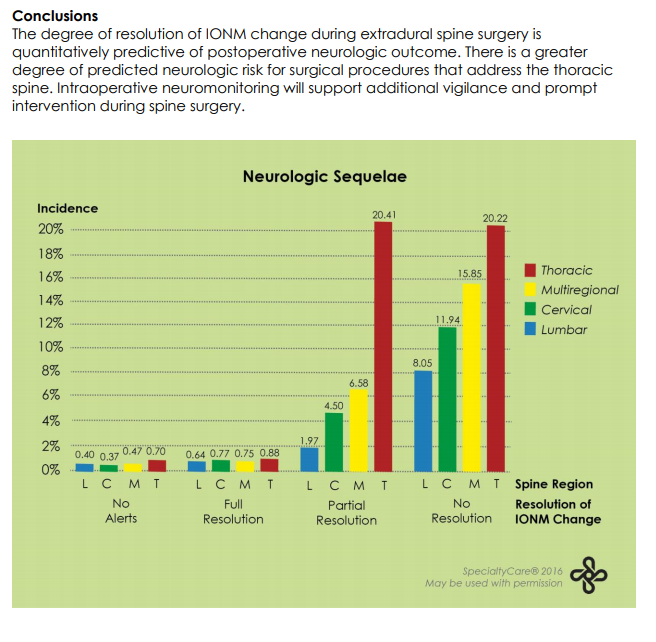

Think about how many cases you and your team do a year and imagine the collective efforts to gather clean data to be used by all in the field. It’s a tall order. This is one I’m with I am intimately familiar, which has almost 70K cases in the study, of which a couple of hundred might have been my own (about 0.3%, just to put things in perspective).

My guess is that most data collected, which varies in degree and depth, falls into dark data — never to be used for analysis.

Even if you’re with a group collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and executing lessons learned, this feedback on the feedback takes time to work through. And then may take more time resetting practice behaviors.

To become both fast and accurate, as master chicken sexers do, we need accurate and timely feedback pointing us in the correct direction. Should the status quo never be questioned, either due to dogma or stagnation, the level of master sexer might always be out of reach.

Suggestions for Chicken Sexer & Surgical Neurophysiologist Success

The advice below takes aim at a couple different groups. First is the individual SNP, because no one is going to care about your career as much as you do. Second are those in a training position, which typically varies on a spectrum of full time to almost never. And third is the organization and its influence over setting the environment.

#1 – Speed Up Your Feedback

Only one way to get it here: ask for it.

Remember, the feedback is only as good as the feedback being given, but also as the feedback taken. That means that you’ll not only need to give your feedback on the feedback given, but you’ll need to have ongoing conversations with the person giving feedback about accuracy. Go back to the checklist above to ensure the feedback is hitting all the marks of effectiveness. If you’re going to hear something most of us don’t want to hear (you’re doing it wrong), squeeze to get every drop of benefit out of it.

This is not about your ego but all about the process. The ultimate goal is not being right, but getting it right.

#2 – Get in Some Extra Reps

There are plenty of opportunities to do this.

Read through research papers on your own. A lot will have images demonstrating the signals of particular cases. Here’s the crucial step: look at those images first and come to an opinion as to what it is you see. Then go back and compare your thoughts as to the points the authors make.

Another option is to ask about helping out with quality teams doing case audits.

Because of HIPPA, you can’t just troll through every case being done at your company. But if you’re there to serve a purpose, like a step in the quality control process, you can increase your speed of growth by looking through case snapshots, discussions, and outcomes. Just scroll through it quickly and come up with a complete summary. Compare your notes to the case notes.

Did you notice something above?

It’s a little off topic, but important enough to mention. I just twice mentioned forming an opinion. Forming an opinion is the active participation part of learning.

Here’s how I’ve used feedback to correct this practice.

I call it FAFO (sometimes referred to as Form A F%*@ing Opinion). If you’re a trainer on a case, the person is there to learn from you. Some, mistakenly, believe the already knowledgeable person does all the talking.

Nay nay.

They are there to ask questions, or maybe lead you back on the correct path should you stray or stall. It is the learner who is there to do the talking and take a stance.

A trainer saying “FAFO” acts as (negative) feedback similar to a clicker. The learner gets the feedback that they are stalling (surgeons love that, right?), giving a wishy-washy answer (surgeons love that, right?), or not delivering information that leads to a solution (surgeons love that, right?).

Saying “FAFO” to week responses is jerky, but only if the intention of the trainer falls short of fully communicated. It’s better to feel that pressure, that sense of failure, under the controlled conditions of a trainer/trainee experience. It takes trust, but it’s worth it.

FAFO in practice works like this:

- form an opinion and give your reason

- what makes you think that?

- what else was eliminated or downgraded?

- defend the likelihood of that opinion (be specific, like “85% likely based on …”)

- what would change your opinion?

- what’s at risk if you’re right or wrong

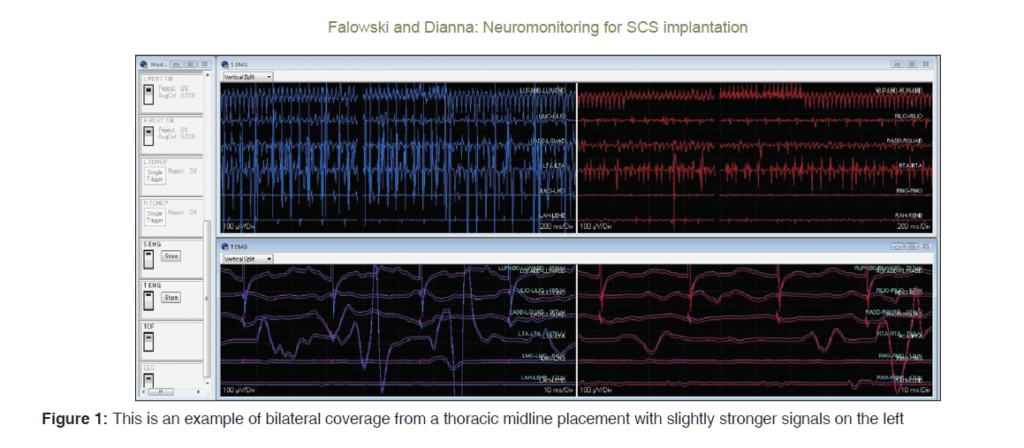

You can do “FAFO” in the OR, but also on extra material. For example, look below at the image from this study. It’s for a spinal implantation case. Here’s your chance to take a quick glance, FAFO, and deliver a compressed communication to a surgeon (and if you can’t do it, this is your clue to go find someone to partner up with who can):

- What’s going on if the spinal implant is on and testing.

- What’s going on if the spinal implant if off.

- What if this was an Ojemann case during stimulation?

- What if this was a tumor removal at the conus medullaris?

Read a book, watch a webinar, watch someone monitor the case, and input the notes. Passive has its place, but active learning is where transformation happens. FAFO is one way to accomplish this.

#3 – Take Account For the Eligible Expenses

Accounting makes measurements easy. Absolute numbers, ratios, comparisons, etc. Those easy to read numbers are legible and managers place a lot of weight on it for decision making.

Organizations (and individuals for that matter) reduce attention placed on eligible measurements. Mostly, because it’s hard to do.

Here’s what I mean. The cost of taxes is legible, and we act to reduce or delay those costs. The cost of poor employee engagement is eligible, and it takes more calories to wrap our heads around that cost. A skilled capital allocator, for example, might see past the short-term capital cost incurred in order to address a collapsing culture. Just as a surgical neurophysiologist playing the infinite game calculate not just salary, but the value of mentorship.

In a world of job hoppers, both organizations and individuals need to better calculate eligible measurements. For companies, neuromonitoring training means building an environment for long-term employment (see #4 below) and for individual SNPs, it means long-term planning, personal branding, and mastery.

#4 -Make It Less About Who Shows Up and More About Who Stays

Spending time, money, and resources spent on neuromonitoring training in the direction of independence in the operating room carries forward from legacy practice. But remember, we’ve switched from scarcity to abundance. Workers are job hoppers as the norm.

As such, it becomes less about finding talented people and more about the continued growth of your current talent in the direction of mastery. Neuromonitoring training is an evolution, not a destination. It’s an ongoing process and the company’s role is the enabler.

Organizations establish the environment. Crafting the destination to mastery as a series of open loops, filled with feedback and rewards, sets in motion a series of open loops. As a loop closes, another opens. This keeps top surgical neurophysiologist engaged and working towards something important. Nothing causes more “stickiness” to something than the feeling of unfinished business. Unfinished business is the result of engagement.

Summing Things Up

As technological innovation continues its deflationary march, cost reduction causes the opportunity of abundance. The job landscape looks different as a consequence. Shifting the focus on neuromonitoring training as a destination (get someone past the CNIM and doing spine) to neuromonitoring training as an ongoing process hedges against the cost of turnover and status quo. Organizations looking to grow through progress invest in the process of clinical mastery and hiring and retaining curious clinicians adept at critical thinking.

As a surgical neurophysiologist, taking ownership in the march of life-long learning gives a new perspective in the value of a neuromonitoring training program. The target hit by offering ongoing and timely feedback by an experienced and knowledgeable team with assets in place to continue grading our decision making. Clues include neuromonitoring training to the CNIM as just a first rung with a long-term plan already laid out.