The CNIM vs The Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Degree

(Joe’s notes: This is a GUEST POST by Josh Mergos, who is the director of the Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Program at the University of Michigan – School of Kinesiology. We met for the first time during a small group discussion about candidates coming out of the Michigan program vs. candidates he’s experienced in our traditional, non-traditional entrance to the neuromonitoring field. Since that Michigan program was so young and not many in the field have even met someone with an intraoperative neuromonitoring degree, I thought that he was probably one of only a handful of people that could have an actual opinion on the subject that was worth much at all. That was the first time I personally met an associate professor or neuromonitoring students, so my opinion isn’t all that valuable (but I’ll still give it at the end).

I appreciated the fact that he was able to take a lot of the emotional element out of his opinion and give honest insight on where their program stands today vs. where they hope to take it vs. what our profession should really want from it. I asked if he would write something for the website that talked a little about the program, as well as his own opinion of where it fits in the field.)

Formal Education in the Field of IONM

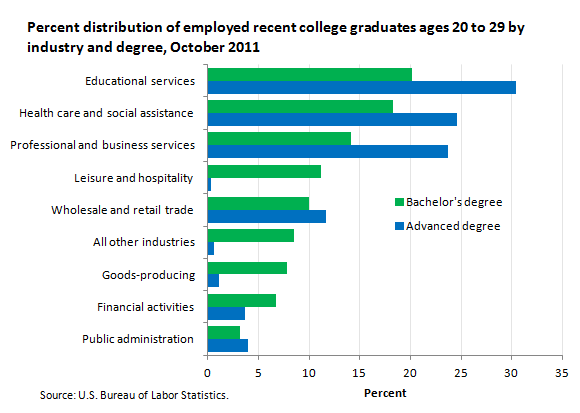

First, a few statistics…in 2011, the bureau of labor statistics reported a 13.5% unemployment rate for college graduates. It’s often said that numbers don’t lie, and while that’s true they can also be deceiving in how they are presented. Looking at the chart below, we see a breakdown of industries in which recent college grads in October 2011, found work. Roughly 20% of these graduates sought work in leisure and hospitality and wholesale and retail trade…..that means that a graduate with a degree in English working at Starbucks is “employed.” If we were to consider the percentage of graduates unable to find work in areas related to their field of study, we would likely find an even steeper rate than 13.5%.

And yet at the same time, the field of IONM continues to suffer from a lack of knowledgeable, experienced neuromonitorists.

Just like anyone else in our field right now, I have a strange, circuitous story as to I became a neuromonitorist. I received my bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the University of Michigan in May 2006. However, just over a month before entering this promising field, I read something quite disheartening. “Eventually the white-collar layoffs will number in the thousands. G.M. employs about 36,000 white-collar workers”. That’s right…the New York Times described my future as an electrical engineer as dismal…not only would job opportunities drastically decrease, but my competition just got much stronger, with thousands of veteran engineers flooding the job market after mass layoffs.

I went back to school and began working on my master’s degree in biomedical engineering, something I had considered in the past. Just one month in I learned about the field of IONM and decided to focus all of my studies on neurophysiology and how it could be applied in the OR. I received my technical training from an experienced group of technologists at a large local hospital and was able to pair this with my concurrent education in neurophysiology. It was an incredible experience, and I am fortunate to have learned about the field at such an early time in my career, and be able to focus my academic efforts on meaningful and pertinent topics such as the differences in electrical excitability of various nerve fibers. I could see how what I was learning applied to the job I was then training to do and my training gave context to what I was studying in the literature or in a lab.

Over the next several years I learned more and more about the field, from both a scientific and structural perspective. It didn’t take me long to realize that IONM was unique for many reasons. One of the strangest oddities I realized was the absence of a standardized curriculum and/or career path. This has indeed stifled progress of the field on many fronts. Yet, on the other hand, it is a rare and amazing thing to attend your most specialized society’s (ASNM) annual conference and to interact with audiologists, biomedical engineers, neuroanesthesiologists, neurologists, neurophysiologists, orthopedic surgeons, and nurses, and to come back with such a multi-dimensional perspective on things. See, it’s the lack of standardization that has fostered, almost by default, such an eclectic composition in our field.

So why try standardizing this? There are two sides to this coin. This absence of standardization has certainly provided opportunities for great collaboration and has expanded the angles from which our practice is approached. On the other hand, we are all likely aware of the all too often incidence of “poor monitoring gone bad” which severely hinders our field’s growth, while underqualified personnel applies poor practices simply because there are no standards or guidelines in place to prevent this. Because of this, it is my strong conviction that our field desperately needs a solid, thorough standard for those performing neuromonitoring. Rather than reinventing the wheel, we can look to other health care fields and learn from their evolution and begin the slow and steady process of bringing standardization to ours. I’ll talk more about that later.

Over the past several years, I’ve had the privilege of discussing these issues with a wide variety of providers in our field and I’ve come to appreciate the unique perspective each brings. I have the utmost respect for these individuals as they have paved the way forward in our field having had less structure to work with than we do now. I’d like to highlight the three main structures that currently exist for neuromonitoring provision (in the U.S.) and following that, discuss how these may change/grow over the next decade and how formalized education ties into these.

The American Board of Clinical Neurophysiology (ABCN) offers a board examination in Clinical Neurophysiology which requires completion of a neurology residency along with a 12-month fellowship program in clinical neurophysiology. Candidates may elect to receive an additional certification in intraoperative neuromonitoring (referred to as NIOM) but there are no specific additional requirements to sit for this portion of the exam. There is currently less than 50 board-certified neurologists with a specialty in NIOM. There are other physician-based boards that interact with the IONM field, but this is perhaps the most active.

The American Board of Registration of Electroencephalographic and Evoked Potential Technologists (ABRET) offers a variety of certification exams that cover specific neurodiagnostic specialties from electroencephalography to long-term monitoring to intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring. For candidates wishing to become certified in IONM by ABRET through taking the Certification Examination in Neurophysiologic Intraoperative Monitoring (CNIM), three pathways to eligibility currently exist: 1) graduation from an accredited IONM or add-on IONM program plus documentation of experience during 50 surgical cases (increasing to 100 next year), 2) employment in IONM with an R.EEG T. or R. EP T. credential plus documentation of experience during 150 surgical cases, or 3) employment in IONM with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree plus documentation of experience during 150 surgical cases plus 15 hours of education in IONM (increasing to 30 next year).

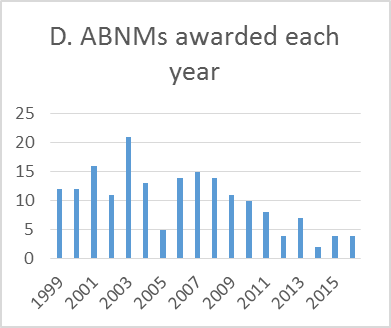

The American Board of Neurophysiologic Monitoring (ABNM) offers a two-step process for certification – a written exam followed by an oral exam. The eligibility requirements to take this exam include a minimum of a doctoral degree in a physical or life science, or a clinical allied health profession as well as evidence of specific formal education in both neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. The candidate must also have experience monitoring 300 cases which include a specific assortment of different types of procedures. There are currently less than 150 actively board certified diplomats of the ABNM (D.ABNM).

One of my aspirations upon learning about IONM was to complete my master’s degree, focusing on neuroanatomy and neurophysiology, and to then sit for the D.ABNM exam. At the time, an M.S., not a Ph.D., was required for eligibility. I missed my window to register and take the exam by just a few months, as I had not yet completed my master’s degree when the change went into effect. Several years later, after speaking with some of those involved with this decision, I must say that I respect that decision and understand that this is part of the process of pushing our field forward, raising the bar.

Over the past several years, the University of Michigan – School of Kinesiology has been developing a bachelor’s of science degree focused on IONM. The program is seated within the Movement Science B.S. the school offers. To learn more about this program, you can look here.

Where then, does a bachelor’s degree program focused on IONM fit into all of this? Does it replace one of these pathways, making it obsolete? Does it add yet another pathway to create more confusion for those making great strides to advocate for IONM’s place as a standard of care? The purpose and goal of this program are to raise the bar, or at least one of the multiple bars present in our field, and arguably, the lowest bar of certification/eligibility in our field.

Regardless of the neuromonitoring supervision paradigm in place, wouldn’t we all prefer that the person in the room have a pretty solid understanding of what exactly it is he or she is doing with those 50+ needles they’ve just poked us with?

Whether it’s a neurology fellow prepping for their board exam, a supervising D.ABNM, or CNIM, the practitioner should have a firm grasp on a variety of fundamentals. And, if these personnel are to discuss the neurophysiologic changes occurring through a case, shouldn’t this conversation be had at the highest level possible?

Here are just a few questions our students encounter at some point during their program:

What are the upper and lower limits of cerebral autoregulation in a healthy adult? What level of cerebral perfusion pressure is kept constant within this window?

What drug is given in addition to neostigmine when NMBs are reversed? Why is this necessary?

Describe the preferred stimulation parameters for sub-cortical mapping. What relationship does current threshold have with distance to the CST?

Explain the neuroanatomical pathway of the BCR reflex.

How many neuromonitorists (those physically in the OR, applying needle electrodes and setting stimulus intensities) currently practicing in the field could adequately answer these questions?

The purpose of this rhetorical question is not to point out any lack of knowledge in some practitioners, but to highlight the inadequacy of the educational model that exists for most neuromonitorists. Some of you may have read the above questions and passed them off as irrelevant. How many of the above answers does one need to know in order to “run the equipment”? Likely only one – the one that involves some type of technical parameter. And if the goal of training a technologist is to ensure their competence to “run the equipment”, these deeper questions and concepts will more than likely be ignored. And therein lies the difference between training and education.

Currently, the purpose of the CNIM is to ensure that the candidate is adequately trained…this is reflected by the types of questions asked. The purpose of the D.ABNM is to ensure that the candidate has been adequately educated on the topics of clinical neurophysiology and neuroanatomy.

Standardized tests are inherently flawed. This doesn’t mean that we should do away with them; on the contrary, they are the standard we use to measure pass or fail…because in many instances in life, we aren’t afforded the opportunity to say “maybe”… we must give a clear cut answer. To borrow an example from our field – the surgeon asks “Can I cut this?” “Maybe” is absolutely unacceptable in this instance. One could try to memorize the right answer or even guess, and in some instances, they just might get lucky…we see this all the time with standardized tests. But the goal is to educate and to teach so that the answer isn’t just a yes or no. It’s a thoughtful question that turns into a dozen “whys” and at the end of the day, something is learned, knowledge is garnered, and progress is made. This translates into a confident yes, which many surgeons who interact with our field have come to demand, some to the point of intentionally doubting or questioning our responses to reassure themselves of our confidence.

To date, 30 students have graduated from the IONM program at the University of Michigan, though it was not until last fall that the program received its initial accreditation from CAAHEP. “What’s accreditation?” you ask. Perhaps I’ll have the opportunity to talk about that and how it plays into certification in another post, as it’s quite complex, but for now if you’re interested you can learn more about it at http://www.caahep.org.

Many fields of practice use accreditation of educational programs as a benchmark by which to screen applicants for what we’ve thus far referred to as certification. Accreditation applies to educational programs whereas certification applies to an individual. Certification almost always involves an examination – written, practical, oral, or some mixture of these. But eligibility for these exams as we’ve seen includes additional criteria.

Of the three basic certification pathways for IONM, only the D.ABNM requires specific topics of study, across both didactic and clinical domains, of the candidate. I personally believe that this specificity is a very good thing. One of the hurdles for those aspiring to earn this credential is this specificity. And the reason for this is that one must seek out this education and experience. In other words, it is not pre-packaged. Perhaps this is why there are currently less than 150 actively board-certified D. ABNMs. This is a problem insomuch that there are simply not enough of these specialized individuals to go around.

Just under 3,600 candidates have successfully passed the CNIM exam since its inception in 1996. It’s difficult to know how many of these certified individuals are still actively involved in IONM, partially due to the large attrition , our field has seen with this position. If we assume a 33% attrition rate, this leaves us with 2,400 CNIMs actively practicing.

The ABCN differs from ABRET and ABNM in that all candidates must hold licensure as a medical doctor. Additional board examinations are taken to display expertise in specific fields, but only the ABCN requires or involves any type of licensure in its credentialing process for IONM.

We are wise to learn from history; and if we observe the growth of the field of nursing over the past century, we can learn much about what worked and what did not; what seemed like a great solution at the time but ended up failing, and what seemed to never be possible but eventually became the standard of practice.

The first nursing association (the ANA – American Nurses Association) was founded three years after a group of nursing advocates met at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. Their primary concern was the discrepancy in education and experience amongst those practicing as “nurses”. Only an approximated 10% of practicing nurses were graduates of a nursing training program. The original purpose of the ANA was to advocate for licensure of the profession. Additional steps were taken to formalize curricula for nursing programs, and an additional association, now known as the National League for Nursing was formed. By 1921, all 48 states (that’s right, Hawaii and Alaska didn’t become states until almost 40 years later!) had passed legislation that provided licensure for “registered nurses.” However, uneducated individuals could still work as “nurses” so long as they didn’t use the title. This issue was exacerbated through the great depression, as licensed nurses had difficulty finding work in a difficult job market. However, nearly 20 years later, mandatory licensure for clinical practice was enacted in 1940.

So here we are in 2016 in a very similar situation. While one cannot directly compare these two fields, as the job market for nursing is much more expansive than that of neuromonitoring, we can observe a similar issue, and that is the lack of licensure.

As mentioned above, the ability for neurologists to provide neuromonitoring services stems from two distinctions, one of which involves a state-governed approval of these practitioners (licensure). Neither D.ABNMs nor CNIMs are approved or sanctioned by a legal entity. And regardless of how vast (CNIM) or stringent (D.ABNM) these certifications become, they will likely not grow in others’ view of their recognition of competency without licensure.

One of the fundamental, key aspects of licensure is standardized education. I’ve been asked if I believe that a university-based program will replace the CNIM or other credentials. On the contrary, absolutely not. Most certification or licensure exams require some type of standardized education from an accredited institution for eligibility. This will one day be a pre-cursor or requirement for exam eligibility and this will pave the way for licensure.

For licensure to work, there must be a strong, unified model to point to as the standard for educational and experiential eligibility. If we advocate for licensure in our field but have no standardized pathway by which candidates can obtain eligibility, we will likely not succeed.

If we create a very broad pathway by which one can achieve eligibility towards licensure, we may gather enough candidates to reach the critical threshold of applicants required to adequately provide neuromonitoring across the entire country, and to require that every individual is certified and perhaps licensed. However, broadening a pathway will most certainly lower the standard required for those admitted. Again, my opinion is that a bachelor’s of science degree + any collection of 100 – 150 cases is far too broad of a margin to set as a bar. Admittedly, I gained eligibility to take the CNIM exam with a bachelor’s of science in electrical engineering and experience monitoring 100 cases, 90% of which were spine. If I recall correctly, only 2 cases submitted in my case log involved BAEPs. Quite a low bar.

I believe that the requirements for obtaining the D.ABNM most certainly result in very highly qualified individuals. That is, the sensitivity of this test is very high…very few false positives. However, given the lack of individuals eligible for this exam (due to lack of clinical education, knowledge, interest or skepticism of the field, or lack of mentorship) I’m afraid that no time soon will there be enough D.ABNMs to reach a critical mass with the ability to standardize credentials and therefore licensure in the field. I do believe that one day in the far, but not too distant future, the D.ABNM will evolve to become the accepted qualifier for the licensed, professional neuromonitorist.

Requiring specific formal education for a candidate to sit for a certification exam adds to its credibility. One of the arguments I’ve heard against adding such a requirement is the exclusion of anyone with no access to this. My response to this is two-fold. First, for our field to thrive, we need several post-secondary educational programs focused on IONM to allow for many aspiring individuals to enter the field, and I think that we are seeing this. Programmatic accreditation will help hold these programs to a specified standard, which is decided upon, revised, and upheld by members of the IONM community. Second, we do at some point need to make this field more specialized, and this will only come about by tightening the requirements for those entering the field.

Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Degree

To date, graduates from the University of Michigan’s IONM program enjoy a 100% job placement rate, most of whom elect to enter the ever-evolving field of intraoperative neuromonitoring.

(Joe’s notes: Here are some additional things to consider to hopefully spark up some conversation:

- If the number of available programs offering an intraoperative neuromonitoring degree and the number of students per program increase over time, then I agree that we will most likely see this as the path to entering the IONM field. This will help bring credibility on a lot of fronts. I really hope that it does away with the term “neuromonitoring tech.”

- I’m glad that the profession was initially integrated into the world of formal education by the caliber of schools that currently have programs and that they are 4-year degrees. It’s going to be a lot easier for this to spread to other areas of higher learning when top schools are leading the way.

- Where I think this model would do a lot for what’s currently considered the CNIM role, it adds questions to the already broken system of oversight. Would schools start to offer a master’s program? What good would that do you beyond owing another $100K in student loans and miss a couple years of income? What about a doctorate? Would that take over the role of D.ABNM as some see it, or would this give oversight privileges similar to medical doctors (and audiologist in some states)? Would there be enough programs in order to pump out enough doctors to cover cases? Would this put downward pressure on the pay scale for the position, which would probably lead to mass exiting of medical doctors from the field?

- There should be a lot more funding available for research in the field with institutions getting grants that private companies wouldn’t. I’d expect to see a lot more research coming out, especially if a doctorate program gets established at some point.

- None of this is happening tomorrow. If you’ve already gone through training that would get you an IONM position, I would never recommend going to one of these programs. The break even point is many, many years off in the future. Go get hired and get trained by the company. If you’re 18 and thinking about this as a career, then I would tell you to consider it. This opinion can, and probably will, change as the field changes.

Josh Mergos

Josh Mergos is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Movement Science and serves as the director of the Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Program at the University of Michigan – School of Kinesiology. Josh received his Bachelors of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from the University of Michigan in 2006 and subsequently received his Masters of Science in Biomedical Engineering from Wayne State University in 2011. Josh’s interests in IONM include the effects of electrical stimulus parameters on peripheral and central nervous tissue excitation as well as spinal cord vasculature.

Want new articles before they get published?

Subscribe to our Awesome Newsletter.

1 Comment

Keep Learning

Here are some related guides and posts that you might enjoy next.

How To Have Deep Dive Neuromonitoring Conversations That Pays Off…

How To Have A Neuromonitoring Discussion One of the reasons for starting this website was to make sure I was part of the neuromonitoring conversation. It was a decision I made early in my career... and I'm glad I did. Hearing the different perspectives and experiences...

Intraoperative EMG: Referential or Bipolar?

Recording Electrodes For EMG in the Operating Room: Referential or Bipolar? If your IONM manager walked into the OR in the middle of your case, took a look at your intraoperative EMG traces and started questioning your setup, could you defend yourself? I try to do...

BAER During MVD Surgery: A New Protocol?

BAER (Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials) During Microvascular Decompression Surgery You might remember when I was complaining about using ABR in the operating room and how to adjust the click polarity to help obtain a more reliable BAER. But my first gripe, having...

Bye-Bye Neuromonitoring Forum

Goodbye To The Neuromonitoring Forum One area of the website that I thought had the most potential to be an asset for the IONM community was the neuromonitoring forum. But it has been several months now and it is still a complete ghost town. I'm honestly not too...

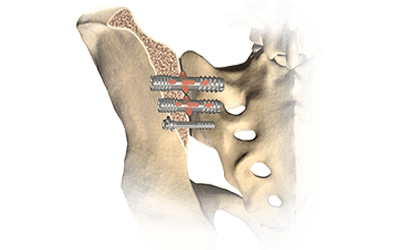

EMG Nerve Monitoring During Minimally Invasive Fusion of the Sacroiliac Joint

Minimally Invasive Fusion of the Sacroiliac Joint Using EMG Nerve Monitoring EMG nerve monitoring in lumbar surgery makes up a large percentage of cases monitored every year. Using EMG nerve monitoring during SI joint fusions seems to be less utilized, even though the...

Physical Exam Scope Of Practice For The Surgical Neurophysiologist

SNP's Performing A Physical Exam: Who Should Do It And Who Shouldn't... Before any case is monitored, all pertinent patient history, signs, symptoms, physical exam findings and diagnostics should be gathered, documented and relayed to any oversight physician that may...

Great article! In my experience, some fields (such as Physical Therapy) are pushing doctorate level programs to achieve several ends, such as direct access, etc. as an effort to bypass physician orders to receive PT. In Neuro monitoring, however, Surgical Neurophysiologists still have to be ‘invited’ into the operating suite by the surgeon performing the procedure, regardless of educational level of the SNP, a practice that will continue to be until intraoperative monitoring achieves a ‘standard of care’ status. That being said, the best paper at 2016 NASS was “Neurologic Outcome Following Signal Change in Spine Surgery”, a paper that highlights the importance of neuromonitoring. That paper is another building block of many that help validate the importance of IOM. When IOM becomes standard of care, the degree program at the University of Michigan, as others that are yet to be formed, will play a much more significant role in standardizing the educational paths of future SNPs. As someone who has personally worked with a graduate of the Michigan program, I’m highly impressed by the results!