Intraoperative EEG For Depth of Anesthesia?

There seems to be some confusion on the effectiveness of intraoperative EEG being able to determine some sort of depth of anesthesia. We seem to find ourselves in this scenario far too often…

“My blood pressure just jumped. Can you look at your EEG and tell me if the patient is getting light?”

What Does Depth Of Anesthesia Mean?

The depth of anesthesia refers to the degree to which the central nervous system (CNS) is depressed. This should encompass the patient’s chances of being alert, the patient’s chance of remembering something and/or the patient’s chances of moving to a noxious stimulus.

There are levels that are outlined when looking at depth of anesthesia:

level 1:baseline recording: awake (premedicated);

level 2:patient sedated, but responsive to calling of his/her name;

level 3:visible motoric responses, either spontaneous or to a noxious stimulus, but no response to calling of a name;

level 4:no visible motoric responses, but autonomous responses still present, either spontaneous or to noxious stimuli;

level 5:no visible motoric or autonomous responses present.

But that is not what is typically being asked of us in the middle of the case. Because we ask anesthesia to allow for movement in many of our cases, they become concerned with patient movement during the case (understandable). So when they ask us if the patient is getting light, they might be asking “is the patient about to move?” That’s level 3, which is deeper than responsiveness.

In fact, when looking at the best way to assess patient awareness is by identification of patient movement.

Right off the bat, a movement to a painful event is reflexogenic in nature. While there is central modulation over the spinal cord from the cortex, it is more than a stretch to think that intraoperative EEG recordings can be used to monitor spinal cord excitability. So there is no way that we can take a look at our EEG and say…

“nope, that patient isn’t going to react to pain at all.”

So we aren’t in the best position to start.

But what about using EEG to better assess patient awareness or wakefulness?

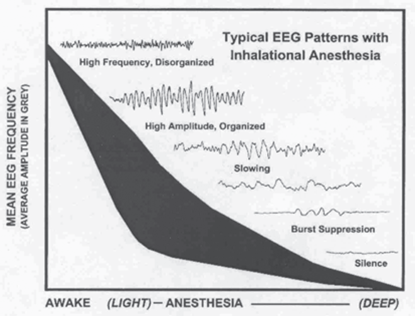

It has been well documented that initial doses of an inhalational agent will cause a desynchronization and acceleration of EEG patterns that will slow and increase in amplitude as the dose is increased. Intraoperative EEG patterns with inhalational agents look like this:

Use of these patterns have been associated with a patient becoming “light” or “deep,”however; there are no criteria that have been found to be sensitive or specific for predicting awareness, memory or movement.

To complicate it even further, real world transition from one pattern to the next is not a smooth curve like the image depicts. There are other factors that can create even more difficulty in interpreting the waveforms and assigning a depth of anesthesia to the patterns generated.

- Intraoperative EEG patterns can often jump levels. And this jumping of levels can be to due to either higher doses of inhalational agents administered or a combination of some other drug.

- Not all drugs have similar patterns. Ketamine and NMDA antagonists (e.g., nitrous oxide) do not produce the typical EEG changes that are seen during general anesthesia.

- Various pathophysiological events also affect the EEG (e.g. hypotension, hypoxia, hypercarbia). Such events may modify both the patient’s level of consciousness and the expected EEG signature that any given anesthetic agent generates, thus confounding interpretation.

Studies have looked at spectral edge frequency with isoflurane and propofol, as well as processed EEG using isoflurane and in a second study. They all came to the same conclusion: EEG is not sensitive or specific for determining the depth of anesthesia.

What really sticks out is that those were in favorable conditions, and there wasn’t mixing of different medications. For instance, opioid analgesics or a combination of agents can cause burst suppression to disappear. Adding a mixed cocktail can also cause an absence in one or more intraoperative EEG patterns or changes in the occurrence of slow wave patterns.

Some facilities might have more strict anesthetic protocols, but the ones I am used to working at vary depending on the provider and patient presentation.

So far I’ve only shown concern for making sure that the patient doesn’t get “light,” but we need to be concerned with the other side of the coin. We should also be cautious when asking anesthesia to increase the amount of agent simply by looking at intraoperative EEG recordings. Placing a patient deeper than necessary is associated with a longer recovery that is also less tolerable. Deep anesthesia brings concerns of other postoperative complications, like mortality, delirium, cognitive decline, dementia, myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure and cancer (controversial).

“Oh, but I only use depth of anesthesia to make sense of my SSEP and MEP”

Using EEG To Quantify SSEP and MEP

This seems to be the more common use of intraoperative EEG for “depth of anesthesia.”

Before I get into it, I just want to offer up a bit of a warning on documentation. Because the terminology “depth of anesthesia” originated and is owned by anesthesia assessing the patient’s state under anesthesia, I would try to steer clear of using that same terminology to discuss assessment of evoked responses under anesthesia. Maybe I’m being a little overcautious here, but I can easily see this being taken out of context.

“The patient moved during the procedure and sustained injuries. According to your notes, you were monitoring the depth of anesthesia. Why did you not alert the surgeon that the patient was getting light leading up to them moving?”

But let’s get back on track here…

Using Intraoperative EEG To Quantify SSEP and MEP

I understand the concept that if EEGs are showing signs of slowing or even moments with isoelectric readings that the brain is metabolically less active. We might also be able to assume that synapses that do not even necessarily reside in the cortex will also be affected by anesthesia and can cause even greater effects on SSEP and MEP recordings.

Where I am having trouble is trying to quantify it to make it useful. I would assume that all the other variables that make intraoperative EEGs difficult/impossible to use to determine the depth of anesthesia would also factor in what we might see in our potentials. Probably even more difficult, because the motor and sensory pathways synapse multiple times areas distant to the cerebral cortex.

But maybe I’m not describing the context of its usefulness like others might… just a round about guess that could possibly explain why global amplitudes increased or decreased in size or morphology from one point in time to the next. Nothing to hang your hat on, you might be wrong almost as much as you might be right and it means nothing without trying to compare it to other findings throughout the case.

Or am I wrong here? Is there a way to use it with some accuracy. I’d like to get to the bottom of what’s being taught and accepted out in the field, so please answer the poll below and then leave an informative response in the comments.

[PS – if you’re for using it and find it helpful, please explain how you use it. “It works for me!” doesn’t work for me as a good explanation.]

Joe Hartman

Subscribe to our Awesome Newsletter.

8 Comments

Keep Learning

Here are some related guides and posts that you might enjoy next.

How To Have Deep Dive Neuromonitoring Conversations That Pays Off…

How To Have A Neuromonitoring Discussion One of the reasons for starting this website was to make sure I was part of the neuromonitoring conversation. It was a decision I made early in my career... and I'm glad I did. Hearing the different perspectives and experiences...

Intraoperative EMG: Referential or Bipolar?

Recording Electrodes For EMG in the Operating Room: Referential or Bipolar? If your IONM manager walked into the OR in the middle of your case, took a look at your intraoperative EMG traces and started questioning your setup, could you defend yourself? I try to do...

BAER During MVD Surgery: A New Protocol?

BAER (Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials) During Microvascular Decompression Surgery You might remember when I was complaining about using ABR in the operating room and how to adjust the click polarity to help obtain a more reliable BAER. But my first gripe, having...

Bye-Bye Neuromonitoring Forum

Goodbye To The Neuromonitoring Forum One area of the website that I thought had the most potential to be an asset for the IONM community was the neuromonitoring forum. But it has been several months now and it is still a complete ghost town. I'm honestly not too...

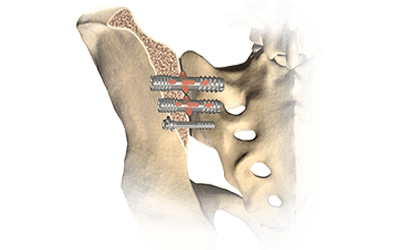

EMG Nerve Monitoring During Minimally Invasive Fusion of the Sacroiliac Joint

Minimally Invasive Fusion of the Sacroiliac Joint Using EMG Nerve Monitoring EMG nerve monitoring in lumbar surgery makes up a large percentage of cases monitored every year. Using EMG nerve monitoring during SI joint fusions seems to be less utilized, even though the...

Physical Exam Scope Of Practice For The Surgical Neurophysiologist

SNP's Performing A Physical Exam: Who Should Do It And Who Shouldn't... Before any case is monitored, all pertinent patient history, signs, symptoms, physical exam findings and diagnostics should be gathered, documented and relayed to any oversight physician that may...

Help Spread The Word. Social Media Works!

Great article. I was looking for something like this and you nailed it.

Thank you, Chrissy.

I thought this article was anecdotal at best and at worst amateur and confusing for the more inexperienced CNIM.

First of all, the purpose of running a modality does not equate to responsibility for a surgical outcome. The job of a CNIM is to inform and document physicians of significant changes in neurodiagnostic data. A CNIM’s responsibility to the data is to have it interpreted by a physician and to communicate that data to other physicians. If EEG data is significantly changed or unchanged that can be reliably communicated and after it is, the onis shifts to the physicians to make a clinical correlation with the data to predict a surgical outcome. To this end, it is always reliably interpreted by a physician that the EEG pattern of burst suppression can reliably determine whether a patient can respond neurologically to pain or stimulus, i.e., is adequately sedated. Therefore communicating EEG patterns is an effective and reliable way for a CNIM to provide a physician with data that can be reliably used to determine depth of anesthesia and can be done reliably without violation of a CNIM scope of practice and exposure to liability.

Thank you for reading and starting up some conversation. It’s probably best for me to respond by chopping up your comment into sections.

“At best” – I did rely some on my experience here. I always do. I think it adds to the article and provides additional perspective. There are other articles where I have less experience, and I will usually put that in the article early on.

But I also have 3 links pointing to published research coming to the exact conclusion of my own experience. So at best, it’s my experience + multiple published sources.

“At worst” – Not sure if this was a shot at me, or just a preface to better prove your point in the next section? We’ll assume the latter.

I agree, to some extent. We’re there to aid the surgeon and hopefully give early warning to potential harm before it happens. But that somewhat understood definition can easily get blurred when being judged by your peers in the court of law (or people without medical knowledge). In that arena, we can share in some of that responsibility. Which is to my point – why take on that unnecessary risk for the sake of nomenclature (for those using EEG to grade their other modalities)? Why call it “depth of anesthesia?” That already has a definition that isn’t the same as what most are intending. If you’re in a case where the patient moved and an injury was caused, couldn’t an opposing attorney see that in your note and start barking up that tree?

Agreed. But please do not assume that this website is read by only SNPs. So the wording is for a broad audience, not SNP specific. That includes those involved in the interpretation of the data.

I’m not so sure that it can. While correlations do exist, there are no parameters found that can be used with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity. Not to awareness. Not to amnesia. Not to immobility. If you’re aware of any such parameters, I would love to learn it. I’m sure every anesthesia provider would as well because those are some of the main reasons they find themselves in court.

If it is burst suppression, is there a specific ratio? Or specific duration of isoelectric potential? Do you need to factor in variables, or does this cover everything? If it was that easy, wouldn’t anesthesia teams all across the country be checking this?

In addition, is burst suppression a desirable anesthetic state to be in for all surgeries? While varying anesthetic protocols will get you there at varying levels of anesthetic depth, to suggest burst suppression for all cases would be a recommendation for an unnecessary abundance of drugs.

I don’t agree here. Maybe I’m wrong (I actually hope I am), but I’ve looked for something to use and have come up with nothing. I’ve asked people what they use, and the answers are usually all over the place, but almost always end up with “that’s the way I was taught to do it.”

Until I see something different, I think your conclusion is potentially misleading to the surgical team, dangerous to the patient, risky for those in charge of IONM services and just bad practice.

This article is also inaccurate in its assertion that the response to a perceived change in EEG should lead to an increase of the agent potentially increasing risk to post operative complications.

While it is true that the post operative complications listed in this article are increased by increasing haloginated agent, the increase of haloginated agent is not the only (and perhaps the worst) anesthetic solution for a patient “getting light” during a surgery. Narcotics and Propofol are always the more preferable options for an anesthesiologist and with adequately maintained blood pressure these options actually aid in managing a patent’s pain and recovery postoperatively.

I’m not sure I would say “always” preferable depending on patient, surgical factors and duration of the case at the point something is brought up. Are those acceptable options, sure. Pretty fast acting too. But those might not always be available (drug shortages and/or cost and/or not immediately available or drawn up) or appropriate.

I know from my own experience I’ve let the anesthesia team know the pt might be reacting to EMG or something and they just swivel in their chair and just turn the canister. So that’s not an unheard of option. That’s why I left it vague without stating any anesthetics in particular.

Multiple channel s-emg firing and unable to run sseps as the cortical /subcortical channels are very noisy is in my view a better way of catching if patient is anestheticly light . In my experience if more than 2 channels of s-Emgs firing the pt moves within a minute . EEG is helpful only if there is a seizure .

Interesting and insightful read. Thank you for providing this content!

Personally, I’m an advocate of EEG as a non-billed support modality during my cases. As you mentioned, it’s difficult to quantify due to variables, but in my experience that is EEG even in the clinical and ICU settings often. The way I view this topic is as follows:

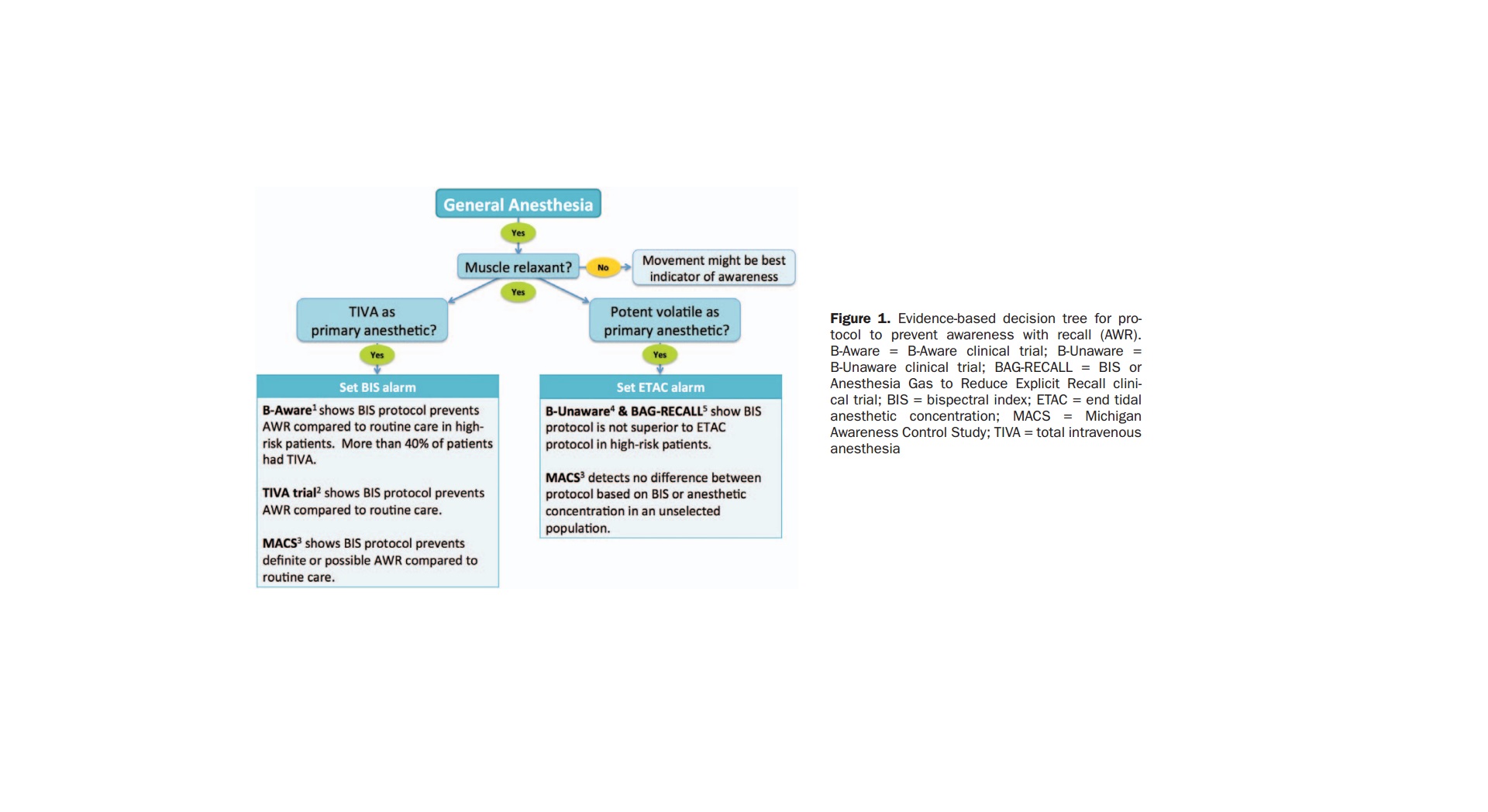

My facility has an excellent working relationship with the anesthesia providers. By default, we use TIVA on all cases involving IOM unless there are risk factors that contraindicate. That said, there is increased risk with TIVA involving awareness with recall (AWR). Other common factors such as age and opioid dependence also increase the risk of AWR. As an olive branch for the inconvenience, I offer EEG to correlate with the BIS readings and physiologic factors that may give anesthesia providers anxiety about depth.

In a recent case, I noticed an increase in the rejection of my SEP signals and switched to the EEG. It was continuous in amplitude and in the alpha-beta range for frequency, which was a stark contrast from the waxing and waning background I saw earlier that was comprised of spindles and k-complexes. I notified the anesthesia provider who told me the BIS was low and she wasn’t worried. After a couple of minutes, my sEMG window began to fire with spontaneous activity, so I went back to affirm the correlation my EEG/SEP had shown earlier. She checked the IV that was infusing propofol and it was running, but not into the patient. The IV had been pulled out and was pooling onto the floor. She immediately switched to gas and thanked me for the help. She now brings an independent EEG machine into her cases (it’s basically a BIS 2.0 though). This was a very experienced attending who I trust 100%.

I offer EEG only as correlation support because I’m not giving my undivided attention to the modality, nor am I billing for it. I use it to troubleshoot acute SEP/MEP changes with no surgical correlation. More times than not I’m able to trace the change back to several boluses of propofol after seeing my patient is “burst suppressed” from what initially was a diffusely slow background with spindling. I find the live EEG “raw” signal to be a useful tool in determining the patients state (in a gross sense) when using it as I’ve describe above.

The tools out there right now are terrible, BIS is terrible, and spectral analysis often gets contaminated, so the data skewed. I’m happy anesthesia providers are considering EEG as a tool, because I believe there is merit in this old modality. One reason you may hear an increase in the request for EEG intraoperatively is due to ICE-TAP (icetap.org); An anesthesia provider driven EEG program working toward understanding depth of anesthesia using EEG. They’re doing a pretty good job in my opinion, but there is still a ways to go.

I don’t want to sound negative towards my own field, but when you breakdown the scientific strength of IOM modalities in general, they look pretty weak (Most fall into class II or III). However, the continual push to refine, research, and challenge convention is what advances science. In the meantime I will continue to use EEG and teach it to my colleagues and students as a resource for troubleshooting. Perhaps one day it will become a gold standard, just as IOM has become for many procedures :)